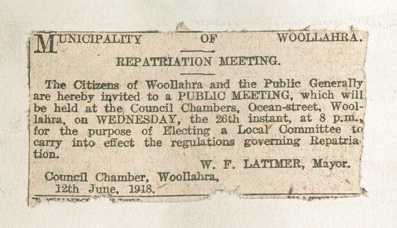

The arrival of men back home from the front was surely the most impatiently awaited event of the immediate post-war period for both serviceman and families. But repatriation as a process involved much more than transporting and welcoming the returned men home. Resettling servicemen into routine life and secure livelihoods was slower and more problematic aspect of the exercise, and one for which local government accepted a partial responsibility.

In 1918, the government determined to replace the "undirected and uncoordinated private effort" to repatriation with a nationally coordinated effort. In submitting the Australian Soldier's Repatriation Bill, Senator Millen said:

We mean by repatriation an organised effort on the part of the community to look after those who have suffered either from wounds or illness as the result of the war and who stand in need of such care and attention. We mean that there should be a sympathetic effort to reinstate in civil life all those who are capable of such reinstatement.

—Ernest Scott, Official History of Australia in the War, Vol.XI., p.833

The Repatriation Department was established to create and coordinate a scheme for repatriation. The department coordinated the provision of pensions for the disabled and for dependents of those who had died; the establishment of employment bureaus, and vocational and rehabilitation training for returned soldiers; and the provision of free hospital and medical care such as artificial limbs for amputees and care homes for the incapacitated.

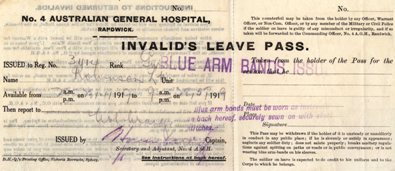

Leave pass from Randwick Military Hospital issued to Leo Whitby Robinson who lost his arm in the war, 1919.

Despite the government run scheme, the work of voluntary groups in supporting returned soldiers - such as fund raising, endowments and practical assistance - was still of vital importance to the repatriation effort.

A group of Double Bay women in fancy dress at a party held to raise funds for returned soldiers, ca.1919.

Finding work

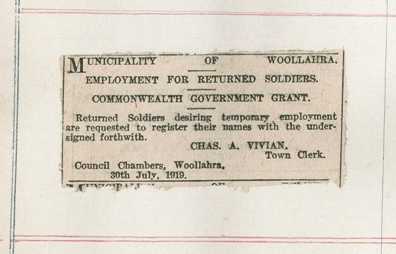

The government sought to provide employment for returned soldiers by enacting the Returned Soldiers and Sailors Employment Act in 1919 which gave soldiers preference and reinstatement in employment. In its bid to help returned soldiers find work, the Repatriation Department enlisted the aid of local councils.

The appeal was greeted with enthusiastic support from Woollahra Council, representatives of which attended weekly meetings of the committees charged with investigating applications by ex-soldiers for assistance in "purchasing furniture, businesses, advances for various purposes, purchasing tools of trade and undergoing vocational training in various trades". The mayor proudly reported in the Council's annual report of 1919 that "great success has attended the efforts of the committees - almost without exception every application has been approved of, and the unemployed soldier is practically unknown in Woollahra".

The Repatriation Department also provided subsidies to local councils to assist them in employing returned soldiers. Paddington Council received £600 for employing men on the 'Barrack Hill Reserve' where "railing and coping were removed, several trees taken out, the branches of others lopped, and the whole area levelled and turfed. Seats were also added, and the reserve made into a useful and ornamental one" (Paddington Annual Report, 1919).

Somewhere to live

With many men returning home with little or no money other than their severance pay, schemes were introduced to assist returning soldiers with finding a place to live. The government introduced the Soldier's Settlement Scheme in 1916 and the War Service Homes Commission in 1918, while the Voluntary Workers Association was established as a volunteer program to build houses in 1916.

Voluntary Workers Association

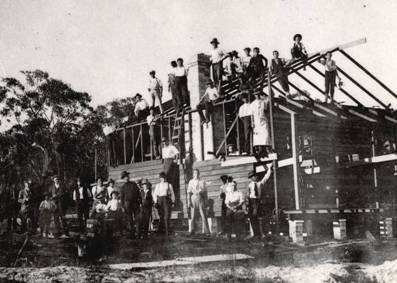

While the soldier's settlement scheme was supporting resettlement in rural areas, there was still a need to find homes for returned soldiers in the suburbs. Towards the end of 1915, crown land in Frenchs Forest was set aside for a soldier's settlement and calls were made for volunteers to clear land and erect houses. The appeal was so successful that the Voluntary Workers Association was formed on 10 February 1916 with the aim of providing housing for returned wounded soldiers or the widows of soldiers.

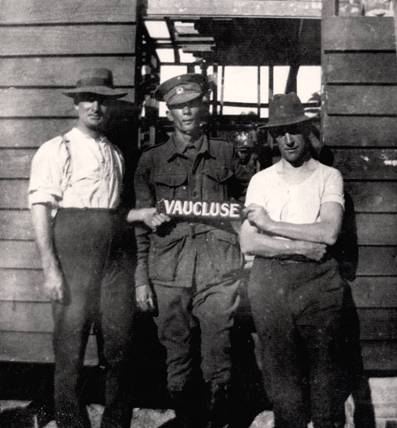

Members of the Vaucluse Voluntary Workers erecting a house at Frenchs Forest, 1916

Dr Richard Arthur MLA, honorary organiser of the Voluntary Workers Association, spent his life working for the less privileged in society and when promoting the Association in March 1916 noted:

...the best way to help disabled soldiers or widows who had nothing but a scanty pension was to make them in a sense independent and safe from the stings and arrows of misfortune.

—Sydney Morning Herald, 29 March 1916, p.12

The Association aimed to find small blocks of land (preferably gifted to the Association) in Sydney suburbs or country towns, on which to build homes and, if the block was large enough, also make provision for poultry and fruit and vegetable growing. The completed home and small farm was presented to the eligible returned soldier who then repaid the interest and principal on the value of the house.

During the next two years, the various branches of the Voluntary Workers Association built over 30 houses on blocks of about 5 acres at Frenchs Forest. The Vaucluse branch of the Association was responsible for the building of one of the first homes at the settlement - a weatherboard cottage for Sgt Harold Buckley who had been sent home from Egypt in March 1915 with tuberculosis. Harold took up residence in his new house in mid-1916 and was reported in the press as one of the success stories of the new settlement (Sydney Morning Herald, 19 March 1919, p.6).

Harold Buckley with two members of the Vaucluse branch of the Voluntary Workers Association, Frenchs Forest, 1916.

By 1917, there were 67 volunteer branches of the worker's association based chiefly in Sydney, and the volunteers included both men and women. By the time of the Peace celebrations in July 1919, the association had erected almost 300 homes across Sydney.

War service homes

By the close of the war, the government recognised the need to do more to assist returning soldiers with finding affordable homes. To help those resettling closer to the city, the War Service Homes Act 1918 was created, coming into effect in March 1919. Under the Act, eligible returned soldiers and their female dependants were able to receive an advance in order to build their own home.

An agreement with the Commonwealth Bank gave the bank the authority to effectively conduct the scheme under which returned soldiers could apply to borrow a set sum in order to purchase land, build a home and make repayments on easy terms.

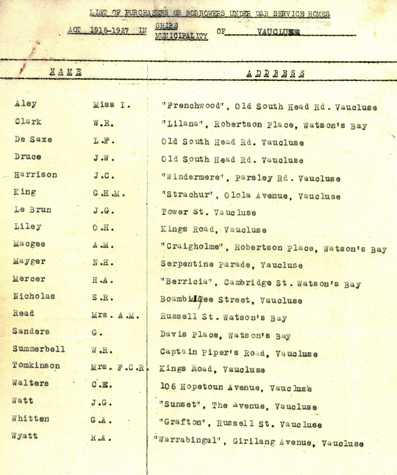

List of war service homes in Vaucluse 1918-1927

The first home was built in Belmore and the foundation stone of the cottage was laid by the governor of the Commonwealth Bank, Denison Miller. Once completed, the house would consist of "four rooms and kitchen" and be "replete with modern conveniences, such as gas stove, bath, lavatory, and verandahs'" (Sydney Morning Herald, 22 July 1919, p.8).

Plans for the homes were prepared by the official architects for the scheme, Messrs. J. and H. Kirkpatrick. John Kirkpatrick was a well known architect of the day who lived at Logan Brae overlooking Cooper Park, and a cousin of the governor of the Commonwealth Bank. John Kirkpatrick and his eldest son Herwald designed over 1700 houses for the war service home scheme in its first 3 years.

War service home built at 106 Hopetoun Avenue, Vaucluse in 1923 for Cedric Walters

In October 1919, an advertisement calling for tenders for war service homes and the "erection of brick cottage residences" listed a number of Sydney suburbs including Vaucluse, Woollahra and Double Bay (Sydney Morning Herald, 1 October 1919, p.9). A list of war service homes in Vaucluse indicates that by 1927 there were 27 such homes in the district.

Well-being

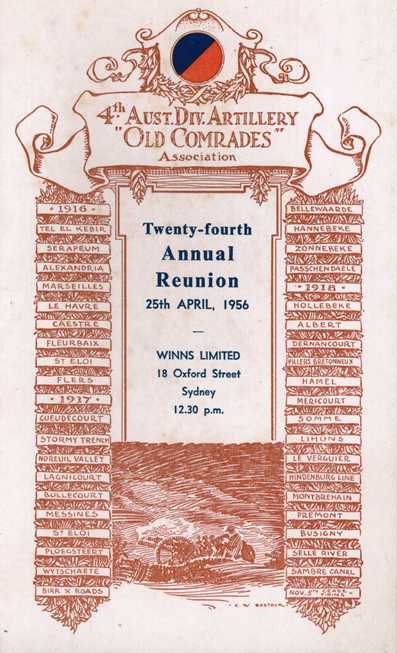

A group of returned soldiers at a reunion dinner (Private collection).

The need for companionship and the unity of shared experiences continued to be important for many men and women after the end of the war. Various returned soldier's groups were established, often close knit groups based on the unit the soldier had fought in.

Leo Whitby Robinson's memento from the 24th annual reunion of his AIF division, the 4th Australian Artillery Division.

It was recognised that a national support group for the welfare of returned soldiers should be created and in June 1916 the Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia was founded. The League (later the Returned & Services League) became a strong mechanism for supporting returned soldiers - particularly in securing preferential employment and in fighting to secure pensions for those injured in war. State branches were formed – NSW in 1917 with sub-branches following, including the local branches of Rose Bay and Paddington-Woollahra.

Rose Bay RSL Anzac Day march along New South Head Road, Rose Bay, 1979 (Photo: Allan West)

Other organisations concerned with the welfare of returned soldiers were also initiated, such as the Limbless and Maimed Soldiers Association formed in 1919.

Limbless Soldiers Association Aquatic Club at Vaucluse

In 1926, a proposal was put forward by the Association to create an aquatic club as it was felt "the best manner for limbless men, especially those with leg amputations - and there were 550 with that disability in the association - to exercise themselves was to engage in water sport, such as swimming or water polo. It was also felt there should be some place where limbless returned men could go at week-ends or whenever they had a few hours to spare. Most limbless men would not patronise public baths and so parade their disabilities" (Sydney Morning Herald, 3 August 1926, p.10).

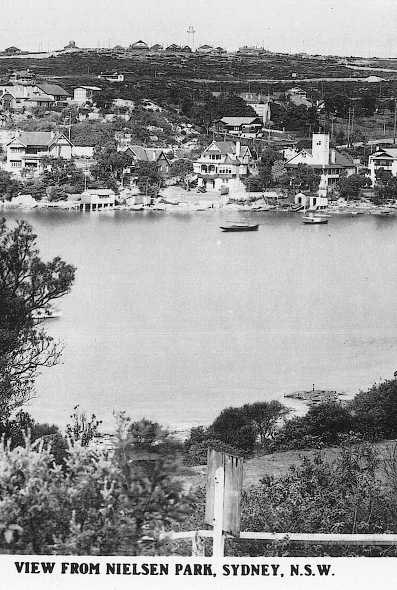

By the middle of the following year, a special committee had secured a site with harbour frontage in Vaucluse and work began on building baths and a club house. The property, at 68 Wentworth Road, already held a two storey home which was adapted and furnished for its new purpose by the association. The Aquatic Club was officially opened on 25 April 1928 by the Governor, Sir Dudley de Chair.

Site chosen for the Aquatic Club on Vaucluse Bay (the waterfront property to the left of the house with the tower); from a postcard, ca 1920.

By 1931, the club was equipped with swimming baths, a boat shed with three rowing boats, a motor boat, an out board motor boat and a sailing skiff, a bowling green, and "in the basement … a sumptuously fitted billiard-room" (Sydney Morning Herald, 23 February 1931, p.11). The 1200 members participated in swimming carnivals, an annual regatta at Watsons Bay, picnics and other social and fundraising events such as card evenings and dances.