The Act

In July 1915, with the extent of the European challenge growing increasingly apparent, the Australian government passed the War Census Act (1915) instigating a sweeping survey of the ultimate resources which might be placed at the nation's disposal for the war effort. Schedule 1 of the Act addressed the need to calculate available manpower, both to supply the war front and to maintain industry and services at home. Schedule 2 addressed the determination of nationwide wealth held in private hands, both corporate and individual.

Males aged between 18 and 59 were the targets of Schedule 1, which required completion of "Personal" census cards posing a range of questions concerning the personal circumstances, age, physical fitness, skills and expertise of its respondents. Schedule 2 required any adult in receipt of an income or possessed of assets to declare them on a "Wealth and income card", with parents and guardians responsible for declaring the income and assets of the minors in their care.

The Commonwealth Statistician, G H Knibbs remarked on the eve of the census:

The public generally do [sic] not appear to realise that practically every person has either to make a return or have a return made on his or her behalf.

—Lismore, Derrinallum and Cressy Advertiser, 8 September 1915, p.17

In the light of this commonwealth concern, local authorities were asked to raise community awareness of the census.

The process

The war census was conducted between 6 and 15 September 1915, administered by the Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics. The onus was placed upon citizens to collect, complete and submit census cards as required, with local postal agencies acting as distribution and collection points. Local councils were asked to play a supporting role by helping residents to understand and interpret difficult questions. The many volunteers who had expressed interest in assisting in the census process were referred to their local council for deployment.

A new recruit has his photograph taken as a keepsake for his family before heading to war (private collection)

Before the close of November, the Commonwealth Statistician was able to report that some 600,000 "fit" men of military age – 18-44 years old – had filed "Personal cards" in the War Census returns. Based on these numbers and British need, the Commonwealth government announced its intention to despatch an additional force of 50,000 men as well as the ongoing monthly reinforcements of 9,500.

The aftermath - the recruitment drives

With the Census declared, recruitment drives began. The nation was divided into recruiting areas, each of which was allocated a quota of men to raise. Recruiting committees were formed at local level and recruiting sergeants appointed. Commonwealth responsibility for encouraging recruitment was now shared with locally organised units providing leadership at community level.

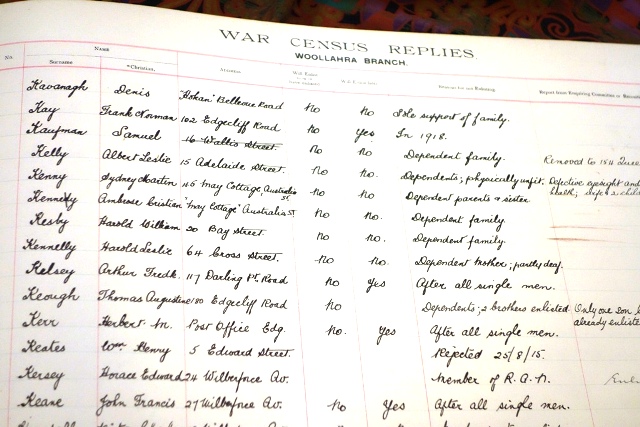

Enlistment cards ("war cards") were issued from the Federal government to Australian men aged between 18 and 45, asking for an indication of their enlistment intentions and an explanation for a negative or noncommittal response. The returns received from men in Woollahra were entered into the War Census volume, including a summary, where relevant, of the reason given for the reply.

The detail filling this volume neatly illustrates the process of this recruitment strategy, from the initial census and "war card" replies, to the local follow up - usually a personal interview - by the local war committee or recruiting sergeant, with notes made at each step. We know from correspondence held in council archives that Lieutenant William O Hug, based at a recruiting office in Bondi Junction, was the recruiting officer for the division of Wentworth which covered the local areas of Randwick, Waverley, Woollahra and Vaucluse.

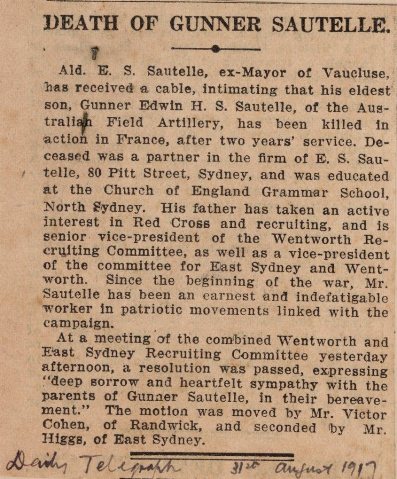

Vaucluse alderman Edwin Sautelle was actively involved in the recruiting drive. His son Edwin enlisted in 1915 and was killed in action in Belgium at age 20 in 1917.

The uncomfortably persuasive power of local involvement was demonstrated by an evident weight of objection which built to these arrangements. By late 1915, with this opposition felt at Federal level, a policy shift was deemed advisable. The concession which resulted allowed respondents to elect to return completed "war cards" directly to the State War Council, provided the local recruitment body was informed of that action. This option circumvented the awkwardness of local scrutiny or, as expressed in the regional press:

[the provision] will, in the case of businessmen, save severe embarrassment

—The Advertiser [Wagga], 29 December 1915, p.2

The final pages of the Woollahra volume are dedicated to a list of over 300 names marked as "Negative replies which are being dealt with by the Central Enquiring committee".

By mid January 1916, the Sydney Morning Herald was reporting that "the majority to whom the appeal was directed have refused to answer the call", and that moreover some replies were "evasive" and others "impertinent". Recurrent "excuses" cited for refusal were, in the order as listed by the Herald:

- When all Germans and alien enemies are interned

- When conscription comes

- When all single men go

- Inability to obtain parent's consent

- Personal obligations

- Conscientious objections

A compelling disincentive to enlistment - evolving public awareness of the high casualty rates

The Sydney-wide pattern cited by the Herald is closely mirrored in the replies given by local men, as detailed in the Woollahra record. To these replies can be added, from the local response, the pleas of the self-employed with businesses to be lost, the concerns of men with elderly parents or disabled siblings to support, the young man who deemed himself medically unfit due to acne, and another who felt himself ineligible due to "insufficient teeth". A surprising number of men were ready to declare that their wives had refused them permission to enlist. Evasive replies were not uncommon and impertinence represented by one local respondent who would not consider enlisting unless offered an officer's commission.

The January 1916 Herald account suggests that Woollahra men were no more ready to embrace immediate enlistment than the men of other Sydney municipalities, reporting that of the "several hundred replies" already received by the town clerk of Woollahra, in only 16 instances had men indicated their preparedness to enlist at once (Sydney Morning Herald, 12 January 1916, p.12). That this early trend continued is resoundingly borne out in the completed War Census replies volume, in which the first column, headed "Will enlist now or have enlisted", is all but filled on every page with entries stating "no", punctuated with an occasional "yes", or an even less frequent note "enlisted" - at least one instance of which is followed by the further note "killed in action".

Taken in its entirety, the document recording Woollahra's War Census replies is a portrait of a community at one of the more divisive periods in the nation's history, when one group of citizens was pressured to make a potentially all-consuming sacrifice on behalf of the whole, with little social latitude allowed for individual choice or alternative viewpoints.

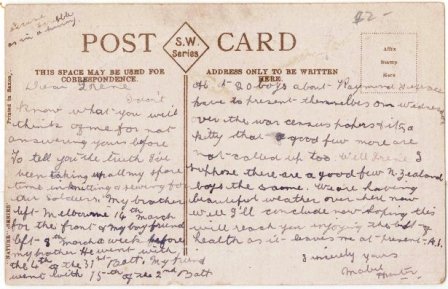

"About 20 boys from Raymond Terrace have to present themselves over the war census papers and it's a pity that a good few more are not called up too. Well Irene, I suppose there are a good few New Zealand boys the same ..."

Words on a postcard in the Woollahra Local History collection