Wintergarden Theatre, Rose Bay

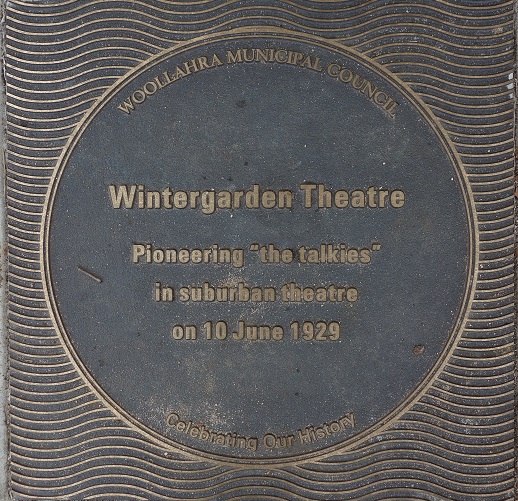

Pioneering 'the talkies' in suburban theatre 10 June 1929

On 10 June 1929, the first public screening of a 'talkie' (sound synchronous motion picture) in a Sydney suburban cinema took place at The Wintergarden Theatre, Rose Bay. The event was the first public demonstration of the Australian Raycophone sounds system, and helped pave the way for the rapid take up of a new technology by the cinema industry in suburban and regional sector.

614-622 New South Head Road, Rose Bay

View all plaques in Rose Bay

Unveiling of Wintergarden Plaque by The Hon. Gabrielle Upton MP, Councillor Anthony Marano and Richard Davis.

A plaque commemorating the introduction of 'the talkies' at the Wintergarden Theatre, Rose Bay, was unveiled on 19 March, 2018 on the footpath outside 614-622 New South Head Road, Rose Bay, the site of the former Wintergarden Theatre, demolished in 1987.

Watch 'Talkie Season Opens: Wintergarden Theatre' (c. 1929) on Australian Screen (NFSA website)

A pioneering moment in 1929 on the waterfront at Rose Bay was to have a cultural importance that extended far beyond the local area. This event was the first public screening of a ‘talkie’ (sound-synchronous motion picture) in a Sydney suburban cinema, which took place at The Wintergarden Theatre, Rose Bay, on 10 June 1929. The event also marked the first public demonstration of the Australian Raycophone sound system, the success of which helped pave the way to the rapid take up of a new technology by the cinema industry’s suburban and regional sector.

The significance of the cinema in the history of twentieth century popular culture can scarcely be overstated. The advent of the ‘talkie’ – as motion pictures projected with synchronised sound were dubbed at their inception – took the already solid popularity of the silent ‘movie’ to new heights, and the history of the motion picture industry in a new direction.

In Sydney, the suburban debut of the ‘talkie’ took place less than two years after Warner Brother’s ground-breaking release of The Jazz Singer in America. The gala event at Rose Bay introduced the ‘talkies’ to an audience which, for the most part, would have been seeing this innovation for the first time. For members of the local industry who were present, an additional focus was the show-casing of the Australian-engineered sound system, the Raycophone, installed and tested at the Wintergarden and subjected to considerable industry scrutiny in the days leading up to the gala screening. The system had been developed by Ray Allsopp, a local sound engineer.

In the weeks following, the local system proved itself up to industry standards, as agreements were forwarded to the Wintergarden (as a theatre outfitted with Raycophone technology) from a succession of major American studios, all undertaking to supply the theatre with films. This was a considerable mark of confidence, given past instances of the big studios withholding distribution from theatres and cinemas which had sourced equipment beyond the studio-developed models. The extremely competitive cost of Raycophone installation saw 375 of its systems rolled out in Australian cinemas by 1938.

Industry recognition of the significance of the Wintergarden’s screening on 10 June 1929 can be measured by the level of interest of its major representatives, further reflected in the presence of two Members of Parliament and the Governor of New South Wales. The evening had a continuing and widespread impact by raising the profile of the affordable Raycophone, which aided the rapid adoption of the ‘talkies’ at cinemas nationwide.

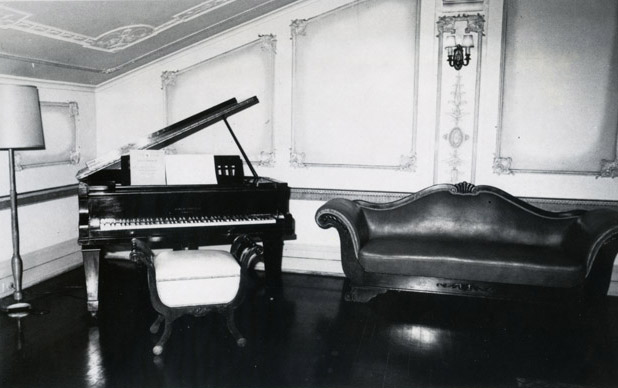

The Piano Lounge, Wintergarden Theatre, 1985.

The advent of American talking movies is beyond comparison the fastest and most amazing revolution in the whole history of industrial revolutions. i

Despite the undoubted hyperbole of Fortune’s statement, the speed of progress in the technology of the ‘talkies’ was remarkable, once the twin hurdles which had stymied Thomas Edison in the 1870s, amplification and sustained synchronisation, were overcome. Australian cinemas were not left behind in this ‘revolution’, adapting quickly to be able to screen the new format – an alacrity which provides the context to the first screening of a ‘talkie’, using an “all-Australian” sound system, at suburban Rose Bay in June 1929.

The driving force in both Australian and American markets was public reaction – a response which surprised many major players in the industry, who had been sceptical about the likely appeal of ‘talking films’. Once exposed to the new technology, the public’s response in America - and soon after, in Australia - ensured that the ‘talkie’ was quickly established as the standard offering in cinemas, wherever the technology was available.

In the late 1920s, the American studio Warner Brothers produced three sound-and-pictures landmarks in as many years. In 1926, as a debut for its partnership with Western Electric in the adoption of Vitaphone sound-on-disc system, the studio added a musical score and synchronised sound effects to its short, silent production Don Juan. The following year, Warner’s produced the feature length The Jazz Singer, which included voiced dialogue and song, and finally, in 1928, the studio produced Lights of New York, a feature-length gangster film that was "all-talking".

The speed was reflected in Australian take-up of the format. Before the close of 1928, in mid-December, a sound system was installed at the Lyceum in Pitt Street, and The Jazz Singer screened on 29.12.1928 – with every step of the way from installation through the system trials to public viewing, feverishly reported on an almost daily basis by the Sydney press

Six months later, Sydney’s still new Wintergarden Theatre was the scene of the first suburban screening of a ‘talkie’ – and with an interesting shift from the Lyceum’s milestone screening, given the city theatre had used the American developed Vitaphone equipment paired with Cinesound. The day after the screening, the Sydney Morning Herald reported

The Wintergarden Theatre at Rose Bay is the first suburban picture theatre to install apparatus for talking films. Instead of putting in American equipment the management has chosen a new Australian device, called the Raycophone, the invention of Mr. Ray Allsopp chief engineer at the 2BL broadcasting station. ii

10 June, 1929 – the first screening

On 10th June 1929, the Wintergarden Theatre was the scene of a gala occasion which would appear to have outstripped in significance its official opening some eighteen months before. In attendance was the Governor of New South Wales Sir Dudley de Chair, and a large contingent from the from the New South Wales Ministry - the Acting Premier, Mr Buttenshaw, the chief Civic Commissioner Mr. Garlick, the Chief Secretary Mr. Chaffey, the Acting Commissioner of Police Mr. Childs, Sir Benjamin and Mr. John Filler. From the Federal parliament, Walter Marks was present; Marks had recently been chairman of a select committee, and then of a royal commission, into the Australian film industry, negotiating the reference of powers between the Commonwealth and States regarding film policy.

The occasion for the local public was the first screening in a suburban cinema of a series of talking films. For the industry, which had also sent representatives, the occasion was the first public demonstration of the Raycophone – an ‘all-Australian apparatus’ (with the exception of imported valves) for playing sound synchronised with the projected image during screening.

Ray Allsop and the Raycophone

The developer of the Raycophone was Ray Cottam Allsop (1898-1972) a sound engineer who presumably had forged his connections with the Wintergarden through his own position at radio station 2BL, which regularly featured the Wintergarden’s orchestra in evening musical programs. The Wintergarden had installed Allsop’s equipment, and industry officials had been present at its various trials in the days leading up to the gala evening on the 10th June.

Born in Randwick, Ray Alsop had been educated at Sydney Grammar before working on various sound-engineering roles in both military and civilian life. The Raycophone brand name combined his first and second names, and the equipment was manufactured in a small factory in Annandale.

The local industry was supportive and impressed with Allsop’s work, and the public and press likewise delighted to find that a substantially Australian system could compare favourably with the American Vitaphone. Assurances of film distribution from the major industry suppliers and studios was the final proof.

The great advantage, for the local industry of the Raycophone, was the cost of its supply and installation – estimated by Allsop’s biographer as the difference between £1,700 for the local model as opposed to some £11,000 for the imported equipment. This had a significant influence on the opportunity for small suburban and regional theatres to take up the new technology and bring the advance of spoken film to their audiences.

The Wintergarden Theatre was built on the Rose Bay foreshores during 1927. The theatre occupied part of the grounds of Clanmarina, built in the 1850s as the family home to John de Courcy Bremer and his wife Eliza. The house and its immediate gardens occupied the greater portion of what is now the Tingira Reserve, while the theatre was built on an area to the east of the house, subdivided from the grounds in 1926.

There is an interesting historical coincidence between the Bremer tenure of the land (c1859-1911) and its eventual association with a noted Sydney cinema and a local breakthrough in the emergent era of the ‘talkie’. Frederick Glasse Bremer, the last of the family to hold the Clanmarina property, was the father of Sylvia Bremer, who as ‘Sylvia Breamer’ established a promising Hollywood career during the golden age of the ‘silent’ film. Breamer’s was one of the many careers in film which did not survive the transition to sound.

The Clanmarina property passed out of Bremer hands in 1911 and entered a succession of ownerships which saw the house variously tenanted, given over to institutional use and eventually renamed Parkside. The Council rate book compiled for 1926 records the transfer of Parkside to John Fraser Jackson, who appears to have held the property only long enough to submit an unsuccessful application to develop the land with nine residential flats, and to subdivide the parcel as the Parkside Estate. Lot A of this estate was sold to Dr James A Lawson - the first reference to the new allotment and its ownership recorded in the 1927 rate book. This allotment became the site of the Wintergarden Theatre.

The proposed theatre excited the enthusiastic commentary of the press, even while the plans still before Woollahra Council awaiting development approval (B/A 534 – submitted by Dr J Lawson). The waterfront location set the project apart, and the view over Rose Bay was one of the most noted aspects of this advance interest. Beyond that, the features singled out for early comment were the scale of the building – sufficient to accommodate 2,000 patrons – and the planned elements of the interior ornamentation, such as a 46-foot dome.

This focus set a pattern, in that throughout its history it was the interiors rather than the exterior presentation of the theatre which received the greater attention. There was a disparity between the relatively plain façade and the grand interior details, such as the indoors fountain, detailed plaster work, and a notable lighting scheme that was much remarked upon in newspaper accounts of the gala opening.

Marble Fountain, Wintergarden Theatre, 1985

The architect for the project was Sydney’s Henry Eli White, who would have been simultaneously working on the abundantly decorative State Theatre which, Heritage listed, still survives today in Sydney’s Market Street. The Rose Bay theatre was restrained by comparison, presumably determined by a combination of suburban setting and budgetary limitations. There was certainly an implication that the Wintergarden project would be delivered in stages, with a ‘wintergarden’ (probably intended for the service of refreshments) to be added. Like this fanciful feature, a balcony overlooking New South Head Road, mentioned in press descriptions of the plans, appears never to have been implemented. The Herald remarked that ‘the cost of the building to the point of allowing entertainments to commence will amount to about £25,000’iii

The Piano Lounge, Wintergarden Theatre, 1985

The Wintergarden theatre had reached that stage by February 1928, and was officially opened on 19 March 1928 by William Frederick Foster, MLA, state member for Vaucluse. The opening program combined live performance with film – a reminder that this was not only a cinema, but a theatre. As well as the theatre’s orchestra, conducted by Lionel Hart, there were segments featuring the solo dance of Miss Edna Saunderson and solo vocals of Miss Dorothy Ewbank. The management paid homage to its location, too, with a ‘gazette’ of local scenes - images of the Rose Bay harbour-front, the local public school, a series of well-known local residents which were projected prior to the screening of the films chosen for the occasion : Gigalo with Rod la Rocque and The Magic Flame with Ronald Colman and Vilma Ranky.

The theatre was rapturously received by the Sydney press, The Sun reporting that the Wintergarden was:

‘in keeping with modern requirements and its locality’ with a 'luxurious interior, novel lighting effects, handsome architectural scheme and general regard to comfort’. iv

Ceramic urn set in a wall alcove, Piano Lounge, Wintergarden Theatre, Rose Bay, 1985

The Wintergarden went on to become a Rose Bay institution, and not only as a social and cultural hub, but a physical presence on the Rose Bay waterfront and the New South Head Road streetscape. Undoubtedly the sheer scale of the building was a factor in this latter standing – a fact acknowledged by the perceived need to camouflage the landmark during the latter years of WWII, lest it present too convenient a target for enemy shells. The proximity of theatre and wartime flying boat base was probably more immediate in official minds than the safety of the film-going public. The firm of Sheedy Brothers was commissioned to create a trompe l'oeil of faux foliage and inter-war buildings along the large blank walls which the theatre presented to harbour and on either side, a device designed to have the theatre visually recede into its harbourfront surroundings.

It is probably not too extreme a claim to say that the Wintergarden gradually assumed an iconic status at local level, and was also much-visited by Sydneysiders from all quarters, delivered to its front door by tram during the heyday of ‘the Watsons Bay run’ and the leisurely notion of a day-trip. As public taste and pastimes changed, as television and eventually the household VCR made an impact, the theatre traded on, creating points of distinction from the George Street precinct’s competition in its programming, making its 1920s architecture and atmosphere a virtue, and serving patrons their coffee in china cups.

Ornamental Window Grille, Dress Circle, Wintergarden Theatre, Rose Bay, 1985

Ultimately, none of this proved sufficient to save the theatre – the cost of maintaining a large and ageing building on the proceeds of a severely declining business saw the theatre sold in late 1980 for $781,000, and sold again in mid-1981. After the second sale, which delivered the property into the hands of a Malaysian-based international syndicate, plans were drawn up for an international hotel on the site. There was a consensus between new owner and authorities that the decaying building and its primary business purpose were both irretrievable.

The voice of protest was at first small and scattered – stray letters to the editor of the Wentworth Courier from individuals with fond memories and a sense of history. However, the unexpected support of local traders broadened the dissent, and a petition raised in September 1981 achieved 700 signatures.

In June 1982 the Wintergarden Action Committee was formed, its aim not only to prevent the building’s demolition, but to ‘support its retention as an entertainment venue’. The group, headed by Andrea Godfrey, staged both a measured campaign of carefully argued written submissions, punctuated on occasion by more attention-worthy acts, to keep the issue alive in the public mind – such as an illegal concert at the site in 1986. The latter aspect was aided by the theatrical talents and enthusiasm of Boom Boom La Berne, who joined the cause towards its end.

The WAC knew some success. An interim conservation order was placed on the site in January 1985, and the BLF (union) came to the aid of the activists and enforced work bans on the site in 1986. But the final effort of the committee’s six year fight - an attempt to challenge, through submission to an official enquiry, the validity of objections raised to the making of a permanent conservation order for the theatre – proved futile, and an appeal to the High Court had to be abandoned due to lack of funds.

The interior of the building was dismantled during January 1987, the walls brought down by a bulldozer on a Sunday morning the following month - 22 February 1987. The building was just one year short of its 60th anniversary.

Beginning of demolition of the facade of the Wintergarden Theatre, Rose Bay, 22 February 1987.

With the site was vacant, the Low Yat group, which had entered into the investment in September 1986, looked for a buyer. The former Wintergarden was acquired by local developer Sid Londish, of Comrealty group, for $9.35. Londish went on to develop the land as a luxury unit block.

Commenting after the battle had been lost, and the theatre demolished, Anthea Godfrey observed

The pity is of course that the State Government and Woollahra Council did not amalgamate the site with Tingira Park as a Bicentennial project. "When you look at what Mike Walsh is doing with the Cremorne Orpheus you realise it was vested interests that prevented film distributors swinging behind us. Suburban cinemas do work and there is a place for them as a community facility. iv

The wisdom of Godfrey’s words has been proven by a thirty year interval. Three decades after the events of 1987, a year which saw the demolition of the Wintergarden at its outset and the re-opening of a restored and revived Hayden Cremorne Orpheum at its close, the Orpheum trades on undaunted, its six screens active, its Wurlitzer organ still played at week-ends, the integrity of its architecture and fittings intact, and its popularity seemingly undimmed.

- i Fortune Magazine, October, 1930

- ii Sydney Morning Herald 11.6.1928 p. 15

- iii Sydney Morning Herald 29.12.1926 p. 6

- iv The Sun 20.3.1928 p. 18

- v Sydney Morning Herald 19.11.1987 p. 7

New plaques are added based on nominations from the community, which are then assessed against selection criteria and researched by a Local History Librarian.

Find out more and nominate a person or event for a plaque.