Herbert Henry (Dally) Messenger

Plaque location

16 Transvaal Avenue, Double Bay

View all plaques in Double Bay

Herbert (Dally) Messenger was born into a family of natural athletes, and raised in a community where sport was fundamental to the local culture. Double Bay, then a village, was to produce a disproportionate number of sporting ‘greats’ of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Of them, Dally Messenger’s name has perhaps best survived the passage of time – familiar even in the mainstream, and in sporting circles accorded almost legendary status for its owner’s exceptional physical skills and the long-held records he created.

Perhaps the most telling indication of Messenger’s stature is that he is recognized by both rugby and rugby league fraternities for his achievements - acknowledged as ‘a rugby genius, ranked the best Australian footballer of all time’ by historians of the code from which he defected in 1907 (Pollard, Australian Rugby Union p. 451) and hailed simply as ‘The Master’ by the Rugby League. That this is so, over fifty years since his death, and more than a century after his short professional career ended, suggests an exceptional legacy.

Dally Messenger’s international standing and record of achievement in the game of rugby added to Australia’s emergent status as a sporting nation. His place in Australian sports history is a defining one, his choice to sign with the new League movement in 1907 influencing the course of the rugby, rugby league and Australian Rules football codes at a critical point in their development.

Family background – England to Sydney

Herbert Henry Messenger was born in Duke Street Balmain on 12th April 1883 to Charles Amos Messenger and his wife, Annie Frances, née Atkinson - one of the eight children of this marriage. Herbert Henry was, and remains, better-known by his nick-name ‘Dally’, its origins lying in an early childhood physical similarity to the portly NSW politician William Bede Dalley, according to Messenger family accounts. Opportunity for this comparison presumably waned in proportion to the growing athleticism of William Bede’s young namesake, who while notably small for a rugby player (168cm/76kg) was fast and agile in the extreme, and unlikely to have been burdened with excess weight. Messenger shed the ‘e’ from his spelling of W.B.’s surname, but used it always, and passed it as the registered given name to his only child, a son, born 1914.

Athleticism ran in the Messenger family. Dally’s father and paternal grandfather were both champion scullers, grandfather James Arthur Messenger (1826-1901) having secured the title of Champion of the Thames in 1854, the same year Dally’s father Charles was born to James and his wife Charlotte. The family lived in the Thames-side locality of Teddington (historic county of Middlesex, now part of Greater London) and James’s occupation is recorded as ‘waterman’ in the parish register where Charles’s baptism is entered. Seven years later, the calling ‘Royal Bargemen’ could have been added, a position James held from 1862 until his death in 1901.

Charles would mirror James’s sporting victories with a number of his own on the other side of the world, and descendants of James Messenger would for several generations continue to pursue maritime-based livelihoods on the waterfront at Double Bay, while maintaining the family’s reputation as skilled oarsmen.

Charles Messenger arrived in the colony of Victoria on the Carlisle Castle in 1875, meeting and marrying in the same year Annie Frances, daughter of William Atkinson and his wife Annie. The couple settled at Emerald Hill (present-day South Melbourne) where the first children in their family were born. In 1879, competing as a Melbournian, Charles easily beat a New Zealand sculling challenger to secure the ‘Championship of Victoria’ on the Yarra, the first of a series of championships won in Australia and New Zealand, which paved the way for Charles’s successful career as a trainer.

By 1882, Charles had relocated to Sydney. His name was recorded in the issue of the Sands Sydney Directory published for that year, listed as a resident of Edward Street, in the Darling Harbour locality. In 1883, the year of Dally’s birth, the directory records Charles Messenger, boat builder, at Princes Street, Ryde. However the Duke Street Balmain address, where Dally is accepted to have been born in April 1883 - and which was the address given for the Messenger Brothers, boat builders, in the 1884 issue of the Directory - was clearly already established by February 1883, when a letter from Charles to the editor of the Evening News was published, Charles giving Duke Street as his place of residence and business.

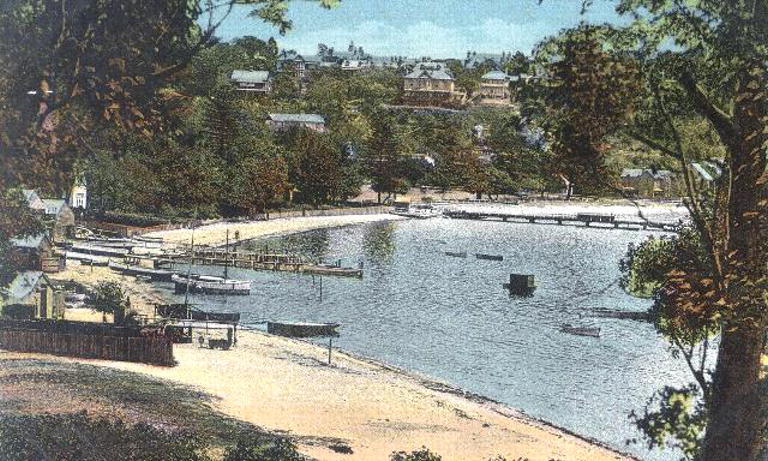

Childhood in Double Bay

Charles Messenger’s family made their final Sydney move, to Double Bay, in 1885. Here the partnership of Messenger Bros - earlier formed between Charles and his brother Herbert Henry (Harry) - established a boat building business on the waterfront which would gradually evolve into a fully-fledged marina, and quickly take on the status of a local institution. The first buildings in this complex were brought from the Balmain site by water, and set up near the foot of Beach Street, where the family made their home. The Double Bay business remained in Messenger hands for three generations, spanning some eighty years of maritime activity.

Dally Messenger attended Double Bay Public School, where both he and his brother Wally were part of an era of sporting achievement fostered by the personal enthusiasm of pupil teacher John Moclair under the guidance of Henry Giles Shaw, the Principal of DPS from 1891-1896. During the Messenger brothers’ period of involvement, the school’s Rugby team was undefeated in inter-schools competition at Junior School level, and from time to time defeated champions from the Senior Schools competition as well. (Hurst Double Bay Public School pp 15-17.)

When not in the classroom, the young Dally spent much of his time in outdoor pursuits, on the water or at the local parks. He excelled broadly in all such activity, and very possibly might have followed a different sporting path with equal success. The renowned Australian cricketer Victor Trumper noted Dally’s natural skill at his own game, and Messenger is credited in sporting lore (dubiously, according to some sports historians) to have, while in play at the Sydney Cricket Ground, performed the possibly singular feat of hitting the clock tower.(Derriman The Grand old ground p. 92).

Dally also shared the family’s inclination for water-based sports, and was an excellent sailor and canoeist. However, Dally himself was quoted as stating, in 1908, ‘I am neither a rower, jumper, nor anything else, simply a footballer’ Clarence and Richmond Examiner 11.7.1908 p. 5).

Early working life and football career

At the conclusion of his schooling, Dally moved naturally into work in the Messenger family business. Football seems never to have been far from his mind, and he would use opportune lulls at the family boatshed to perfect the full length dives which he used to such effect on the field, plunging repeatedly head-first into an old car tyre. In games he was known to dive over the top of would-be tacklers to score – a move which incorporated a somersault.

Messenger played his first competition games at suburban level with the Warrigals, a team of predominantly Woollahra players, formed in 1899 and based at Centennial Park. Messenger joined the side in 1900, and in 1902 played alongside another future representative player and all-round athlete, Reginald Leslie (Snowy) Baker. The team was runner-up in the competitions of 1901 and 1903, reaching the semi-finals in 1902. In published reports of their games, notwithstanding the presence at times of the great ‘Snowy’ Baker, one Warrigal player was outstandingly singled out for comment: Dally Messenger. (Hickie, The Game for the game itself. pp. 38; 192)

In 1905 Messenger was persuaded to join the Eastern Suburbs Rugby Club, an opportunity which led to play at representative level, both state and national, during 1906 and 1907. Easts had formed in March 1900 at a meeting at the Paddington Town Hall dominated by influential names, and had built an early strength in club rugby by strategically signing up gifted athletes : Harry Flegg, Snowy Baker and Olympian Stan Rowley among them. It was an affluent and powerful club - ‘the haven for the more notable …who wanted to be part of Sydney’s most flourishing sporting code. (Growden, Greg The Snowy Baker story Syd., Random House, 2003 p. 31.)

Messenger captained the reserve grade team in his first season with Easts, and moved into First Grade representation in 1906. Here all the hallmarks of his talent were finally on broad display - not only his physical prowess but his mental agility and creativity. He quickly established himself as the biggest ‘drawcard’ which New South Wales rugby had to offer, which made his defection to the fledging code of Rugby League the following year, in August 1907, a bitter blow not only to Easts, but to the New South Wales Rugby Union. Gate takings were vital to the survival of any code, and Messenger with one move had transferred a good proportion of the available pool of spectators to the embryonic League.

Messenger was unsurprisingly expelled from the NSWRU – instantly and for life - and so deeply was his disloyalty felt that his name and achievements were struck from the organisation’s record books. It was not until June 2007, all but a century later, that the NSWRU voted to restore Dally’s name for the record, posthumously welcoming him back into the fold, in honour of his accomplishments and the role he had played overall in Australian sport. The Chief Executive of NSWRU remarked at the time that to do so was an easy decision, ‘The only pity is that he's not around to witness for himself the game embracing him once again.’ (www.abc.net.au/news/2007-06-24). Messenger had died some forty-eight years earlier.

Move to Rugby League

The two agents of the local Rugby League credited with luring Dally Messenger to switch allegiances were Paddington cricketer Victor Trumper and sports enthusiast and entrepreneur James Joseph Giltinan, one of the founders of the New South Wales Rugby Football league, and its first secretary. Also instrumental in the decision was the mother of their target. With the untimely death over two years earlier of 52-year old Charles Messenger, his widow Annie is believed by her descendants to have taken the leading role in her son’s decision, apparently persuaded by evidence of the NSWRU’s failure to adequately compensate injured players. (Heads True blue p. 46)

The signing of Dally Messenger took place at the Messenger family home on the Double Bay waterfront on 16.8.1907, according to Messenger family history. If the date is correct – and it has been queried (Heads, p. 46) – then it was the very next day that Messenger was on the field at the Sydney Show Ground, playing in Australia’s first ever League match against the New Zealand ‘All Golds’. The home team was billed simply as ‘Australia’, and was comprised of many leading defectors from the NSWRU. The crowd of 20,000 was achieved largely due to a last-minute welter of promotion based on Messenger’s appearance. On the strength of his play, Messenger was invited on an English tour with the All Golds, noted by one football historian as ‘an extraordinary tribute from players regarded as the world’s best’. (Pollard p. 455)

A family background in the world of sculling, where professional sportsmen were an accepted fact of life, would have made the transfer from amateur status quite natural for Dally, untrammelled by qualms about the ‘player-gentleman’ schism. Nonetheless, given his seemingly casual approach to his personal finances, it is doubtful that he would have been unduly influenced by the prospect of payment, even had the fees not been the modest sums on offer by the embryonic NSW League. He famously turned away from lucrative offers from English soccer officials, and the story is told of how, on hearing that James Giltinan was facing bankruptcy over the 1908-1909 Kangaroo tour, Messenger tore up the contract which had secured him his fees for the matches played (Pollard p. 456).

Messenger, from 1908 until his retirement from professional football in 1913, played for The Eastern Suburbs District Rugby League Football Club. Formed in January 1908, ‘Easts’ is one of the foundational clubs of the New South Wales League, and the fourth to form. During his time with the club, Messenger led the team to victory in three premierships (1911, 1912 and 1913).

The speed of Rugby League’s ascendency in Queensland and New South Wales is generally linked directly to Dally Messenger’s willingness to adopt the new code as his own. Sports historians surmise a further ramification: that the rise of the League halted the northerly march of Australian Rules football, which it is believed would have otherwise gained overriding popularity with the demographic already captured by league football.

Influence of the Double Bay locality on Messenger’s sporting achievements

The Double Bay of Messenger’s youth was home to a widely diverse community of sports enthusiasts and achievers. Dally’s brother Walter (Wally) followed his brother’s lead to play club, representative, state and test football, and fellow Bay resident Sid (Sandy) Pearce was a League player of note, to whom Dally Messenger paid tribute as ‘the greatest hooker the world ever saw’ (Truth 14.4.1940 p. 10). The suburb also numbered among its sporting successes the Ashton family’s polo triumphs in England, the test career of accomplished cricketer Hunter ‘Stork’ Hendry, and the Olympic achievements of other members of the Pearce family in sculling, and of Dick Cavill in swimming.

Impromptu neighbourhood games of any sport were a routine part of the Bay’s culture. Dally recalled in an interview for the serialised Truth biography published 1940, his carefree days with the local ‘scratch’ team of barefoot footballers, known as the ‘Seaweeds’.

The Double Bay community was tightly-knit, and the Messenger family had, within a single generation’s residency, married into another Double Bay family with sporting achievement to its name, with the marriage in 1902 of Dally’s uncle Harry with Susannah Pearce. This was a pattern repeated in subsequent generations, as Dally’s sisters Willa and Ivy married rugby-playing brothers William (Bill) and Charles (Charlie) Lee. The intermarriage between sporting families concentrated the focus on sport, and gave it additional prestige at both a family and neighbourhood level.

In this era of Double Bay’s history, public tribute at a community level rewarded local sporting achievement - such as the testimonial organized in 1885 by the Double Bay citizens to mark Charles Messenger’s training of a world champion sculler, William (Bill) Beach (Evening News 31.3.1885 p.6). Dally himself received, after his return from an English tour, a decorative address welcoming him home, organized by a committee of Double Bay residents and written ‘on behalf of numerous friends, admirers and well-wishers in Double Bay.’ The citation read

When we review the names of the athletic champions produced by New South Wales in the cricket, rowing swimming and boxing world we feel that no name has added more glory to the fame of our country than your own on many a hard fought football field.

It is difficult to imagine that an environment in which sport inspired such sentiment would not have had an impact on the young Dally Messenger, giving him both the impetus and the licence to devote the time and energy required to perfect his footballing skills to the level he achieved.

Retirement from professional football and later years

On 14.10.1911, Dally Messenger married Annie Macaulay, née Carrol, in Sydney. It was presumably no coincidence that Messenger began to scale back his involvement with professional football shortly before that time. To the disappointment of many football followers, he withdrew from a tour of New Zealand scheduled to sail two months before his marriage. He then declined selection for the 1911-1912 Kangaroo tour of England. From September 1911 onwards, reports in the regional press were concerned with Messenger’s increasing talk of retirement, ultimately realised at the end of the 1913 season. Dally was farewelled by his fellows with a testimonial dinner, and a grateful Easts presented him, as a personal memento of his play, the premiership shield, won by the club three times in consecutive years and each time under his captaincy. The Royal Agricultural Society Challenge Shield – black mahogany with silver mountings – is now in the collection of the National Museum of Australia, its citation reading, ‘The shield's association with the genesis of rugby league in Australia, and its connection to the game's first great superstar, make it one of the most important rugby league objects held in a public collection in Australia.’

Public reaction to Dally’s retirement was mixed, with some media comment commending the good judgement of a decision to step away at the peak of a career. However, Dally also suffered something of the backlash familiar to all public figures when adoration begets ownership, and there was inference here and there of a selfish and opportunistic choice, made at a time when Dally was ‘far from doing his dash …to spend more profitable time at the beer pump than at potting goals’. (Sydney Sportsman 18.9.1912 p. 1) The ‘beer pump’ was a reference to Dally’s wife’s proprietorship of a city hotel, The Albion, which he managed alongside her for some years.

There had been a similarly jaundiced tone in parts of the press when Dally and Annie Messenger enjoyed a belated honeymoon in February 1912, the Richmond River Herald remarking tartly: ‘Dally Messenger, the famous footballer who decided to forego a trip to England in order to marry a rich widow in Sydney, is now off an a jaunt to Java with his wife.’ (22.2.1912 p. 3)

In retirement, Messenger tilted without great success at a number of careers – including banana farming in Buderim, Queensland and hotel-keeping in Sydney and elsewhere. In July 1917 the Daily Observer newspaper, published in Tamworth, NSW announced that Dally Messenger was taking over a hotel in the nearby town of Manilla: ‘The Royal Hotel, previously Mrs Swaine’s.’ (11.7.1917 p. 3). Almost immediately there followed reports in regional newspapers of Messenger’s involvement in local Manilla sport – a wartime benefit rugby match for the France Day fund, and some district rugby matches with Dally playing for Manilla against nearby towns and localities. A report published in the Sydney newspaper, The Arrow noted that the regional areas of New South Wales were ‘content to mingle codes.’ (11.7.1917 p. 3). Finally, in May 1919, came the announcement, ‘League football will be played at Manilla this year …Dally Messenger is the captain of the Manilla team’ (11.7.1917 p. 3). It would have been a great moment for the small town, and an opportunity for Dally to continue doing what he liked best – playing the game.

In the same year however, Dally’s small family was struck by personal tragedy, brought upon them by the great 1919 pneumonic influenza epidemic. On 20.6.1919 the Adelaide Daily Herald reported that both Dally and his wife Annie were ill, and the hotel placed in isolation (p. 4), and the following day, press reports described Dally’s condition as ‘serious’. However, it was Annie Messenger and not Dally who, like many other young victims of this post-war virus, lacked the physical resources to fight it. She died several days later, on 23.6.1919, leaving Dally the sole parent to their small son (Daily Observer 24.6.1919 p. 2).

Beyond her value as a wife and mother, Annie Messenger had enjoyed the advantage of a family background in hotel management, experience now lost to her widower. He remained at the Royal Hotel Manilla for a time after his wife’s death, but by 1925 had returned to Double Bay. Dally’s homecoming was not to the immediate waterfront locality of his childhood, where the other Messenger family households were clustered around Marine Parade and Stafford Street, from Beach Street to Castra Place. He instead settled to the west of William Street, living at No 16 Transvaal Avenue for the next five years (Sands Sydney Directory 1926-1931).

Messenger married Annie (Nancy) Thurecht in Sydney in 1927, and in 1932 moved from Transvaal Avenue to No 14 Glendon Road Double Bay (Sands Sydney Directory 1932). However, provided with a grace-and-favour room at the headquarters of the Rugby League in Philip Street, Dally ultimately spent much of his time in the city.

The Richmond River Herald, fourteen years after commenting on the providence of Dally’s marriage to a ‘rich widow’, remarked in an apparent about turn, ‘It was a bad day for Dally when he took on the hotel business, for with ordinary care and restraint he might have been able to sit back on a comfortable fortune by this,’ instead of which, as the writer observed, ‘Dally Messenger, The Master footballer of all time, formerly a hotel keeper in Manilla, is today an employee of the City council – a carpenter’(7.9.1926 p. 3).

This stark dichotomy between Messenger’s football and post-football years is a theme taken up repeatedly in biographical accounts of the man. Perhaps a rugby player has captured this best - Herbert Moran, Captain of the Wallaby team which toured in 1908-9 when the first Kangaroos were also in England. Noting Messenger as ‘one of the very great three-quarters of all time’, Moran goes on to say of him, in football retirement,

Somehow all the world went wrong with him, and later, while his name still lingered on footballs and football boots, the man himself was forgotten and fell upon hard times. Like a great Catharine-wheel he had flared and sputtered with a dazzling white light, then suddenly faded out, a dark thing lost in the darkness.

(Heads, p. 47)

Despite his post-football years being seemingly lacklustre, Messenger was not quite as forgotten as Moran asserts. The newspaper Truth embarked on an account of his career in 1940, which ran to fourteen instalments. And Dally spent his City days reliving his past glory in the Club’s precincts, and giving considerable pleasure to many rugby enthusiasts who wanted to meet him in person. At the entrance to the club’s committee rooms was a full-size portrait of him, unnamed and undated, and captioned with the only information needed: ‘The Master’ (Pollard, p. 459)

Dally Messenger died, aged 76, on 24 November 1959 while staying in the regional NSW town of Gunnedah, where a local publican was pleased to provide grace-and-favour lodgings on a basis similar to the city Leagues Club’s arrangement. After a funeral service at St Mark’s Darling Point, crowds lined the streets in tribute as the cortege left the church for the Anglican Cemetery Botany. It was a clear indication that the Master was still remembered.

Career strengths and legacy

Dally Messenger’s career was comparatively short. With his coming to grade and representative play later than he might have, and retiring when aged just 30, it is the spectacular nature of his play rather than the longevity of his involvement for which he is held in such esteem. He was known for his ability to kick goals over an extraordinarily long range, and to be as nimble with one foot as the other – once kicking a field goal with his left foot while being held in a tackle by his right (Pollard p. 459).

With the sport in its infancy, Messenger was also able to exploit many openings since closed off by the institution of specific rules – some introduced directly as a result of his inventive play. While noted for his extraordinary speed and acceleration, it was his ability to evade defenders and confound his opposition which set him apart as ‘The master’, and which made him such a compelling player for his spectators.

Dally’s tactics didn’t always suit club and national officials, or selectors, whose intentions he routinely overrode in play, drawing on the prerogative of captaincy if he felt his strategies would bear fruit. Nor did he necessarily please fellow players, who sometimes felt robbed of their own opportunities by Dally’s relentless possession whenever he judged his retention of the ball to be the likeliest route to success.

Messenger was not insensitive to his shortcomings in team work, acknowledging this flaw when praising a later player as ‘a wonderful team man’ and adding, ‘now, when I was playing, I was a fair coot to play with, as my old teammate Dan Frawley will tell you’ - a reference to Frawley’s comment that ‘nobody but Dally knew what would happen when he got the ball, his teammates often as mystified by Dally’s moves as the opposition’ (Heads p. 47).

Nevertheless, Messenger’s single-minded dedication to winning games delivered results which stood for remarkable intervals of time. In the 1911 season he kicked 108 goals in 20 matches, and scored 270 points, a record which remained unbroken until 1935.

Tangible mementos of Messenger abound. His likeness was chosen in 1936 to represent Australian involvement on the Courtney Goodwill Trophy, Rugby League’s first international trophy, which depicts players of four nations: Australia, Britain, France and New Zealand. In his home town, a stand at the Sydney Cricket Ground is named for him, in honour of the games he played at that venue, where he was also the first footballer to be made an honorary member. A life-size bronze sculpture of Messenger was created in 2008 by sculptor Cathy Weiszmann and installed outside the Sydney Football Stadium.

Other honours include the Dally M Medal, presented annually to the Australian rugby league player judged the best player of the season, and Messenger’s admission into the Australian Rugby League Hall of Fame in 2003.

Sports historians have drawn on the many superlatives heaped upon Messenger by writers who actually saw him play, and these are too numerous to be sensibly quoted in any comprehensive way.

Sources

- The Australian Encyclopaedia of Rugby League Players: every premiership player since 1908/ Alan Whiticker and Glen Hudson, rev.ed Smithfield NSW Gary Allen 1995 p. 205

- Cuneen, Chris ‘Herbert Dally Messenger’ Australian Dictionary of Biography Volume 10, Melb., Univ., Pr., 1986.

- Derriman, Philip The Grand old ground; a history of the Sydney Cricket Ground. Nth Ryde, Cassell, 1981.

- Hickie, Tom The Game for the game itself. Syd., Sydney Sub-District Rugby Union, 1983 pp. 38; 192.

- Heads, Ian True Blue : the story of the NSW Rugby League Randwick, Ironbark Press, 1992 p.46

- Hurst, Mary Double Bay Public School 1883-1893: the first hundred years Syd., DPS 1983 pp 15-17.

- Martin, Tom ‘Marine Structures in Woollahra’ Woollahra History and heritage Society Briefs, No. 50 1993

- Pollard, Jack Australian Rugby Union: the game and its players Syd., A&R/ABC, 1984 p. 452

Unpublished sources

- Transcript of an Oral History Interview of Hunter Hendry with Margaret Brownsombe, (Interviewer) Syd., WMC 1984.

- WMC Rate Books

- Trove – Newspaper collections, National Library of Australia

Nominate a person or event

New plaques are added based on nominations from the community, which are then assessed against selection criteria and researched by a Local History Librarian.

Find out more and nominate a person or event for a plaque.