I feel it is my duty to report that history was made last night when Woollahra was shelled from the sea. The defence authorities report that the shelling was carried out by submarine.

Mayor of Woollahra, Mayoral Minute, Minutes of Woollahra Council, 8 June 1942 p. 207

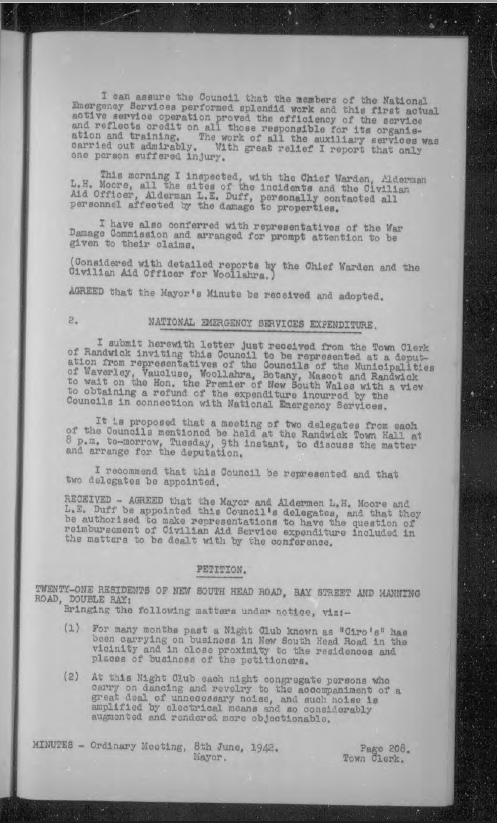

Badly damaged rear of the house at 4 Bradley Avenue, Bellevue Hill, 1942. Image: Australian War Memorial No: 012594

Alderman Keith Manion was the Mayor of Woollahra in the year of the Japanese shelling of Sydney, and the author of the Mayoral Minute that recorded the broad detail for posterity.

Woollahra Municipal Council Minutes 8 June,1942 page 207.

Woollahra Municipal Council Minutes 8 June,1942 continued .. page 208.

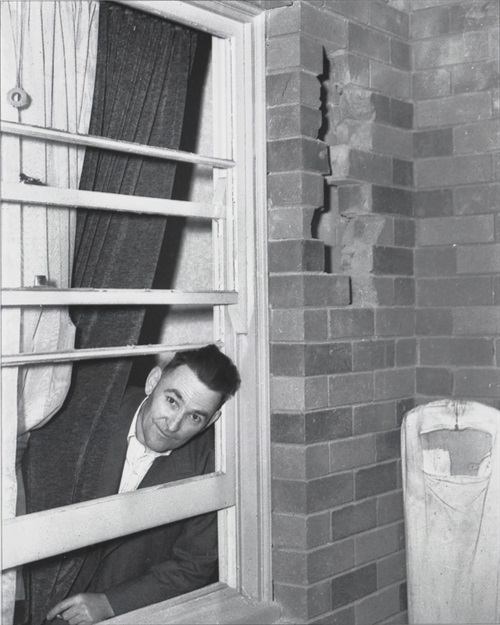

Also present at the Council’s meeting of the 8 June – an ordinary meeting, part of Council’s regular schedule - was Alderman Lyle Moore (Chief warden for the local district) Alderman Leslie Duff (Civilian Aid officer) and Alderman Reginald Thornton, duty warden on 7 June, whose shift had officially ended just before the shelling, but who turned back for further duty when the sirens sounded soon afteri.

Alderman Reginald Thornton, warden on duty on the night of 7 June,1942. Image: Woollahra Libraries Digital Archive PF001486

These men – and no doubt others of the 12-man Council – had been galvanised into practical action by the events of the early hours and their aftermath, inspecting sites of damage and liaising with authorities on behalf of owners and residents of affected property. Council’s headquarters, then at 90 Ocean Street Woollahra where the meeting of 8 June was held in the upstairs chamber, also housed on the ground floor the wardens’ control room for the district. Here the duty warden maintained a central point of communications for the warden posts dotted across the municipality, an arrangement which placed the Council administration at the centre of these and related operations.

90 Ocean Street, Woollahra which housed the Woollahra administration until 1947. Woollahra Libraries Digital Archive PF006360/0980.

For all those involved in the efforts carried out on the night of the Sydney shelling, and in its immediate wake, the event no doubt appeared the harbinger of much to come, from further raids to full-scale invasion. Hindsight allows us to conclusively dismiss their apprehension.

As Australia’s then most populous city, capital of its largest economy and accorded a tacit seniority as the Federation’s oldest European settlement, Sydney might well have been considered a prime target for swift and decisive humiliation by Japanese forces, such as Japan had proved capable of delivering elsewhere. In fact, Sydney escaped lightly in the war of the Pacific. The sum total of military assaults was a raid on her harbour by three Japanese ‘midget’ submarines on the night of 31 May/1 June 1942, and the shore bombardment which made history for Woollahra a week later.

Of these, the harbour raid resulted in the sinking of an RAN depot ship, HMAS Kuttabul, and the deaths of twenty-one young sailors sleeping aboard when she sankii. The shore bombardment resulted in isolated damage to private property and public roadways, minor injuries to several residents, and the death of a USAAF pilot responding to orders. Neither event occasioned the loss of civilian life, nor created any effective disruption to daily routines or the national war effort.

HMAS Kuttabul after the explosion, 1942.

When Terry Jones and Steven Carruthers set out to compile the most detailed and meticulously researched account yet published of the bombardment (A Parting shot, Casper, 2013) they discovered gaps and inconsistencies within even official record gathering, and in the realm of personal anecdote, a need to dismantle myth before they could assemble facts. The authors concluded that despite their research, some aspects of the night seem destined to remain the topic of debate and ongoing conjecture unless credible new sources emerged.

What is well established from multiple sources about the events in Sydney is that shortly after midnight on the morning of the 8 June 1942, a Japanese I-class submarine, I-24, under the command of Hanabusa Hiroshi, fired ten rounds from a position some six miles off Malabar.

Estimates of the time taken to deliver the shells differ. The Official war history puts the duration at five minutes, based on sightings of gunfire in the relevant location by HMAS Adele at 12.15am, and a conclusion of fire at 12.20am.iii A conflicting estimate based on reports from shore observation posts, and quoted in Jones’ and Carruther’s A Parting shot, suggests an assault that lasted for between two and four minutes.iv

The I-24 had surfaced shortly before midnight to carry out this assignment, the shells from which would land chiefly in the suburbs of Rose Bay and Bellevue Hill, with all but one of the ten falling within the boundaries of the municipality of Woollahra. The beam from the Macquarie Lighthouse, a landmark adopted by the municipality as a symbol of the area and its administration, had given critical assistance to the crew of I-24 in the orientation of its assault.

Badly damaged rear of the house at 4 Bradley Avenue, Bellevue Hill, 1942. Australian War Memorial No: 012595

The Eastern suburbs bombardment was one-half of a ‘paired’ assault, in line with Japan’s noted modus operandi. A week earlier, the midget-submarine raid on Sydney Harbour had mirrored a midget-submarine raid on the Madagascan port of Diégo-Saurez, carried out by the Japanese the day before the Sydney Harbour attack.v

The action which was paired with Sydney’s shore bombardment was closer to home. At 2.15am, a little over 2 hours after I-24 had fired ten shells on Sydney, a second of the Japanese I-class submarines, I-21, under the command of Matsumura Kanji, surfaced in Stockton Bight and fired on the city of Newcastle. Estimates of the number of shells fired at Newcastle varies from thirteen to thirty-four,vi including an unknown number of ‘star shells’ fired to provide illumination rather than inflict damage. The official war history sets the figure at twenty-four rounds, fired over twenty minutes, the attack ceasing once fire was returned from the shore.vii

The onshore response came from Newcastle’s Fort Scratchley, which would end the war as the only Australian shore establishment to have fired on an enemy warship off the Australian coast. The damage in the northern steel city was similar to Sydney’s toll – no deaths, negligible injuries, some property damage and nuisance disruption to operations at Newcastle’s steelworks.

The submarine I-24 which shelled Sydney in 1942 was part of Japan’s Eastern Advance Detachment, a squadron made up of three B-1 Scout submarines and two C-1 Attack submarines, commanded by Captain Hankyu Sasaki. The large craft variously carried ‘midget’ submarines (I-22, I-24 and I-27) or reconnaissance planes (I-21 and I-29).

The mission assigned to the squadron when it left Japan in April 1942 was to launch midget submarine operations to locate and destroy large naval targets of the enemy (nothing smaller than a cruiser), to disrupt sea-based enemy supply lines and to engage in shore bombardments.viii The raid on Sydney Harbour fell into the first of these categories, with a number of worthwhile targets in the Harbour confirmed during a reconnaissance flight by Susumo Ito before the decision to launch the attack was made.

The shelling of Sydney’s east fell into the last category of these orders. It has been observed that the Japanese submariners typically reserved shore bombardment for the close of a campaign.ix

Mochitsura Hashimoto, who was the torpedo officer on the I-24, provides some insight into the likely feelings of the crew and commander of I-24 as Commander Hanabusa Hiroshi positioned I-24 ready for the assault.x Mochitsura’s explanation of the inherent risks faced by crew in the exercise of gunfire on a shore target allows us to imagine the sense of dread as the moment of fire approached.

The first risk was posed by the inevitable time taken to load and fire the submarine’s deck gun - time which could allow shore batteries to effectively make sightings, calculate range and return fire. The second was the catastrophic risk that, in the event of an emergency dive, the ammunition hoist hatch – able to be closed or adjusted only from the outside – would be imperfectly sealed at submersion.

Jones and Carruthers point out that Commander Hanabusa had first-hand experience of the dangers of this exercise as he approached the execution of the Sydney bombardment. Five months earlier, on 25 January 1942, he had been forced to crash dive to escape fire returned from a US base, having discharged only five of an intended seven shells at targets off Midway Atoll. As it happened, the US base had been forewarned by Allied intelligence before the January attack, but in June 1942, as he faced an unprepared and unsuspecting Sydney, Hanabusa could not have known about their advantage, and may have anticipated a similarly swift counter attack.xi

He need not have worried. On 8 June, the submarine's ten shells were fired before Sydney deployed searchlights, let alone retaliated. Orders complete, the I-24 retreated out of range, no doubt to the overwhelming relief of Commander and crew.

A disturbance in suburbia - the shelling as seen from the land

Onshore, it was a rude awakening on many levels for the residents of areas where the I-24's ten shells came to rest. Their arrival was unsettling even when, as was most common in this event, the shells failed to explode, landing with a heavy thud and often burrowing into the soil to a depth of up to six feet. The loud whistling of their delivery was remarked upon in multiple accounts – often described as a ‘screaming’.

The three shells which exploded left significant craters on impact, while the associated blast inflicted damage on adjacent buildings. While there was no wholesale destruction, the sight of the partial ruin of Nos 4 and 6 Bradley Avenue, Bellevue Hill would have provided a sobering indication of the force of an explosive weapon – a demonstration outside the experience of most residents of these peaceful suburbs.

While there has been a certain amount of debate and inconsistency in accounts, it has been reasonably well established that the following places and outcomes of the shelling are accurate to the events of that day:

| Shell |

Location |

Outcome |

| 1 |

26 Manion Avenue, Rose Bay |

Unexploded |

| 2 |

3 Plumer Road, Rose Bay |

Exploded |

| 3 |

67 Balfour Road, Rose Bay |

Unexploded |

| 4 |

81 Beresford Road, Rose Bay |

Unexploded |

| 5 |

9 Bunyula Road, Bellevue Hill |

Unexploded |

| 6 |

4 and 6 Bradley Ave, Bellevue Hill |

Exploded |

| 7 |

Cnr Small and Fletcher Streets Woollahra |

Exploded |

| 8 |

Woollahra golf links, Rose Bay |

Unexploded |

| 9 |

Royal Sydney golf links, Rose Bay |

Unexploded |

| 10 |

34 Simpson Street, Bondi |

Unexploded |

Shell damage in the southern wall of 26 Manion Avenue. Australian War Memorial 012583.

Reports of an eleventh shell having landed in Olola Avenue Vaucluse were unable to be substantiated at the time, and were later discredited. Residents of the locality in June 1942 were confident that there was no truth to this rumour, and after more was understood about the submarine operation it became clear the area would have been beyond the range of I-24’s known position and firing capability.

Jones and Carruthers suggest the confusion arose from the misinterpretation of an accurate communication received at 12.22am from a warden at a Vaucluse post, and recorded in the log book of the National Emergency Services. The message reads simply ‘a bombardment from the sea, now in progress.’xii The municipality of Vaucluse, while host to defence bases, key military installations, and the strategically significant entrance to Sydney Harbour, escaped the war unscathed.

As the shells fell in the early hours, residents reacted with confusion and disbelief. While panic was minimal, neither was there an orderly response. In many cases bewilderment and denial kept residents in their houses rather than their shelters – and neglectful of the brown-out restrictions, to the consternation of wardens. Tales were told of residents who would not leave their homes without first conducting time-wasting searches for important documents or treasured possessions.

One story of indecisive action leading to a distressing and potentially dangerous situation was told by Elsie Moore to The Sun newspaper.

“I heard four shells come over and I decided that if there were any more I would go to the air-raid shelter. The fifth came but it was so cold out that I changed my mind. Next moment the world seemed to crash about my ears as the sixth shell exploded on the road below.”

Quoted from The Sun in A parting shot p. 47

Mrs Moore’s bedroom in an enclosed veranda in Yallambee Flats, was strewn with shattered glass, broken bricks, shards of road bitumen and other debris from which she sustained minor injuries and no doubt considerable shock.

While many were slow to react, others had no warning to heed. At Grantham Flats at the southern end of Manion Avenue, home by chance to three wardens, notification arrived via the first shell, which pierced the double-brick outer wall of the building’s southern elevation. The shell continued on a crazy path via the Hirsch family’s flat, piercing internal walls before coming to rest, unexploded, on the building’s common staircase.

The five occupants, including an eighteen month old and an elderly woman, were showered with debris as they slept, but all escaped unscathed apart from Edward Hirsch. An electrical engineer who had fled Europe pre-war to find a safe haven for his family, he now found himself on the other side of the world as the only civilian casualty registered from the Japanese attack.

Amidst citizen chaos, the local services appear to have carried out their work with calm efficiency.

“I can assure the Council that the members of the National Emergency Services performed splendid work and this first actual active service operation proved the efficiency of the service and reflects credit on all those responsible for its organisation and training. The work of all the auxiliary services was carried out admirably.”

Mayor of Woollahra, Mayoral Minute, Minutes of Woollahra Council, 8 June 1942 p. 208

Not all services received such accolades. While it had little effect on the ultimate outcome of the events, the unpreparedness of Sydney – her people and her defences - was revealed by the Japanese attacks, and Sydney’s light escape must be seen as in many ways a matter of chance, coupled by enemy action which was never intended as part of a fully-fledged assault.

Perhaps the most criticised was the failure at the highest level of naval command in Sydney to heed reports of an unidentified aircraft over the harbour at 4.20am on 30 May, and to consider its potential significance as a reconnaissance flight. In Diego-Saurez, a similar sighting had led to Allied defences taking action, moving the anchorage position of likely targets. In Sydney, a number of important Allied naval assets were left open to destruction had the midget-submarine raid been carried out more successfully by the enemy.xiii

With the May 31 attack underway, defence communications within the port of Sydney were shown to be generally deficient, with runners despatched to give key orders which could not be delivered by telecommunications. Also questionable was the deliberate decision to allow ferries to run as usual, in the hope that this general activity might deter the submarines from surfacing until daylight - but thereby putting civilian life in danger.

Despite the harbour raid delivering what should have been a ‘wake up’ to Sydney defences, similar confusion confounded the counter operations on 8 June. Admittedly, the speed at which I-24 fired her rounds from a cautious position gave the onshore guns little time to react. Nevertheless, any lost opportunity is regrettable when viewed in the context of the havoc wrought by Japanese submarine activity in Australian waters during the Second World War. This was frequently disruptive of supply lines, and resulted in a heavy loss of life among merchant seamen.

A more immediately distressing example of unpreparedness on 8 June was the manning of the US Army Air Force squadron of fighter aircraft, based at Bankstown aerodrome. Despite the fact that the entire Allied command assumed that, if attacked, Sydney would be bombed from the air, there was only one member of the fighter aircraft crew available on base when counter action was ordered. Squadron Commander Lieutenant George Cantello crashed soon after take-off – his death believed to have been a consequence of his haste to become airborne as the sole responder. The loss of this twenty-seven year-old serviceman was the only death recorded as a result of Japan’s sea bombardment of Sydney.

1st Lieutenant George Leo Cantello, Commanding Officer of the 41st Pursuit Squadron, USAAF, based at Bankstown Aerodrome, lost his life as a result of the shelling of Sydney AWM p05600.001

As for Japan’s Eastern Advance Detachment, the results of the two attacks on Sydney were disproportionate to the Japanese losses, all of which arose from the Harbour raid: six skilled sub-mariners and their craft, and a reconnaissance float-plane whose pilot and ‘spotter’ survived the rough landing.

The bombardment in context - Sydney’s light escape, Japan's muted success

To place the two attacks on Sydney during World War 2 into proportion, we need only make comparisons with the casualties, damage and deaths suffered in attacks on other parts of the Australian mainland during the conflict, and the fact that some areas were attacked multiple times - Darwin, Broome and Townsville among them.

The most extreme comparison is with Darwin which, on 19 February 1942 suffered two major air raids, in which an estimated 683 bombs were dropped, with between 250 and 320 deaths resulting, and between 300 and 400 casualties inflicted. Ten ships were sunk, twenty-three aircraft destroyed, and great damage to other military assets and civilian property exacted. Moreover, this was only the beginning of repeat assaults, with Darwin and areas surrounding the town the subject of 62 further raids.

Broome also suffered. In one of three raids carried out on the port, a strafing attack in March 1942, some eighty lives were claimed - the death toll inconclusive given the unknown number of refugees from the Netherlands East Indies sleeping aboard Flying Boats destroyed at anchor.

Put into context, Sydney’s escape was indeed light, but it does not follow that the attacks were totally without achievement for the Japanese, at least when viewed in terms of the likely motive for the shore bombardment, once understood by historians.

While the objectives and targets of the midget submarine raid on Sydney Harbour were obvious to Allied observers, the reason for the shore bombardment was more mystifying. Many targets for the shelling were put forward over time as the primary one – and each discounted. With time and distance from the events it has been concluded that there was no single target or objective, and it has been noted that Tokyo Radio on the day of the bombardment referred to Japanese submariners using their guns to ‘blaze haphazard’ at Sydney and Newcastle,xiv This description provides a vital clue to the real intention.

History was denied the chance to form a cohesive understanding of the wartime plans and decisions of the Japanese command with the almost wholesale destruction of official documentation of the period. However, testimonies and statements presented at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in the late 1940s provided new insight. Subsequently, personal reminiscences and direct accounts emerged from former Japanese servicemen, each giving fresh perspectives on the overall rationale.

Two survivors of the submarine detachment, Mochitsura Hashimoto from I-24 and Susumo Ito, the reconnaissance pilot operating from I-21, are quoted in Jones and Carruther’s A Parting shot in frank commentary that suggested the psychological impact of the attack was always the main purpose of the shore bombardment, and the likelihood of striking a specific target understood to be very low.

Japan had an appreciation of the uses of psychological warfare, and while her “Tokyo Rose” broadcasts were considered clumsy propaganda by young American servicemen of the 1940s, the broadcasts showed a degree of sophistication in their execution which suggests the effort was believed to be worthwhile. The Sydney bombardment provided an opportunity to deliver fear through direct, ‘serious’ military action to what was no doubt assumed to be a suggestible civilian population, and with it an illusion that worse was to come.

As for the threat of a real invasion, a sworn statement of wartime Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Togo at the time of his testifying at Ichigaya, was that it was realised as the war progressed that Japan lacked the resources to mount and sustain an invasion of Australia.xv It was hoped that, rather than by military conquest, Australia might be persuaded in a newly realigned post-war world to adjust her vision to accord with Japan’s ‘New Order and Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity’. However, Japan calculated that an Australia flagging in morale, and needlessly frightened of a phantom invasion, would be a less focused, committed and useful support to the Allied forces. The explicit aim of promoting a mass evacuation from centres with an already depleted workforce was another likely part of the plan, as a means of further undermining the war effort.

In this regard the effects of the bombardment were mixed. There are many examples of Sydney residents who sent their children to stay with country relatives, and housing prices were said to have fallen dramatically – although in this respect it is difficult to separate the specific effects of the bombardment from the general dampening effects of the war. Complementing vacancies in Sydney property, areas such as the Blue Mountains noted a swelling of the population, supporting the idea that Sydneysiders moved to escape further raids.

However, there was no organised or official undertaking to relocate women and children out of the coastal belt of New South Wales, and many Sydney residents were determined to stay. War historian Paul Hasluck saw the threatening events of the first half of 1942 as awakening Australia to ‘a fuller realisation that it was a nation at war’ - but suggested it was an awakening with a positive result.

“The major effect of bad news was … to stiffen the resolution of the people to face and to survive the perils of war. In the camps, at their work, on ARP patrol or in their homes they were a happier and a more closely knit people than they had been since war began. They knew they were standing on their own ground. They waited for the Japanese to come.”

Hasluck, Paul The Government and the people, 1942-1945. Canb, AWM, 1970 p. 69

Mrs Maisie McEachern, with her husband in military camp and both sons serving abroad, was living alone when the rear of her Bellevue Hill house was blasted into rubble by shell no 6. She refused to move out from the remaining section of the ruins, even on the night of the shelling. ‘My house is still standing. I don’t see why I should go elsewhere.’ was her reply to the suggestion.xvi

While militarily irrelevant and mercifully unsuccessful if measured purely on a scale of physical damage inflicted, the June 1942 bombardment of Sydney nevertheless made a significant impression upon the small population of wartime Woollahra. Of the ten shells which fell, nine landed within the municipal boundaries, three of which exploded. Forty years later, when Woollahra Library embarked on an Oral History project to capture the memories of residents across a diverse range of local topics, it was a rare interviewee in a position to remember that event who had no personal story to tell. Accounts of the incident also intersperse a series of World War II recollections published by the Woollahra History and Heritage Society in 1995 to mark the 50th anniversary of the end of the war, and feature in individually published biographies of eastern suburbs residents. Here are three stories of varied experience from Woollahra:

Some slept through

Not everyone experienced the ‘rude awakening’ which the I-24 set out to deliver.

Two who slept soundly were Bellevue Hill resident Nina Barden and her husband, a serviceman home on leave from the army. Nina wrote of their experience in 1995

“I can well remember the night that Sydney was shelled by the Japanese submarine – or rather the next morning. I heard someone walking past my home in Vivian Street Bellevue Hill say, ‘What do you think? We were bombed last night’. So I said to my husband, who was sleeping, ‘Wake up Darling, we were bombed last night’… We were indeed startled to find that several flats in Rose Bay had been hit, as well as a home nearby, No 4 Bradley Avenue”

Barden, Nina ‘A War bride’, As I remember: recollections of World War II p.32

Overshadowed by a family loss

For one local family, a moment of personal grief that was quite unrelated to the enemy attack, would distinctly lessen its impact. Eighteen year old Vince Marinato had been summoned home by his family from militia service in Singleton, in regional New South Wales, with the news that his grandmother was dying. He reached the family home, Rosaria, in Watsons Bay shortly before midnight, to find his grandmother had died before his arrival, and went to pay his respects by her side in the front bedroom of the family’s Marine Parade house.

“Peace was rudely interrupted by shell bursts, followed shortly after by the piercing wail of air-raid sirens – it was the night that Sydney’s eastern suburbs were shelled.

I walked out onto the veranda listening to the shells whistling in the night. People were running along Marine Parade.

The house cellar had been heavily sandbagged and it was the street’s unofficial air-raid shelter. I remember one elderly neighbour arriving, her hair done up in curlers and in her dressing gown with her jewellery box under one arm and a loaf of bread under the other. I vaguely remember somebody, maybe Tony Bagnato or Uncle Ossie, calling out for me to go into the shelter.

I spent the remainder of that cold early June night in lonely vigil by my grandmother’s bedside, the only lights visible to me were the four candles at each corner of her bed. I fell asleep in the chair beside her.”

Marinato, Vincent The Shop on the wharf p. 97

A chance meeting

Marie Dyer was a Bondi teenager in June 1942. In 1998, in a compilation of eastern suburbs reminiscences, she recalled the Japanese bombardment of Sydney in these terms,

They peppered the eastern suburbs with mostly unexploded missiles, one of which fell a few streets from my home…

but her attention was reserved for another event,

In a fraction of some second between 8:14am and 8:15am on the bright summer morning of August 6th, 1945, a bomb containing the destructive force equivalent to 20.000 tons of TNT exploded over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. It released the forces of heat and radiation onto the 260,000 people estimated to be in the city on that day.

Dyer, Marie ‘I still have his photo’ in I remember, I remember p. 6

Dyer had visited Hiroshima in 1948, ‘two years and eight months’ after the atomic bomb had been dropped. While she had in August 1945, in Australia, ‘rejoiced with the rest of the world at the end of the fighting’, the visit to the ruined city would haunt her.

This once thriving industrial city was a maze of torn, twisted buildings, rubble, collapsed bridges and mile upon mile of newly erected barracks to accommodate the thousands who had been left homeless. Petrified trees stood as ghost sentinels to the effects of the conflagration. It was feared that not a blade of grass would grow for 75 years.

Dyer, Marie ‘I still have his photo’ in I remember, I remember p. 6

Buying fishing tackle soon after in nearby Iwakuni, Dyer was provided with a chance meeting which tied together for her the two war-time events. The shop’s owner, in conversation through an air force interpreter, was revealed to be Susumi Ito, the pilot of the reconnaissance plane which had identified the targets in Sydney Harbour before the May 31 midget submarine raid.

The two felt an eerie connection with the realisation that, at one point in the early hours of May 30 1942, as two young people on opposing sides of a war, ‘Mr Ito had probably flown over my Bondi home.’

Fifty years after the meeting, when she shared her memories in a Woollahra Council publication, Marie Dyer still held the picture of a brave young Japanese reconnaissance pilot, and hoped that fate might provide an opportunity for them to meet again to reminisce.

As I remember : recollections of World War II by members of the Woollahra History and Heritage Society and the Eastern suburbs division of the Legacy Club of Sydney. Sydney, WHHS, 1995

Gill, G Hermon Royal Australian Navy, 1939 – 1942. Canberra, AWM, 1957

Gill, G Hermon Royal Australian Navy, 1942 – 1945. Canberra, AWM, 1968.

Hasluck, Paul The Government and the people, 1942-1945. Canberra, AWM, 1970

I remember, I remember: Senior Citizens of the Woollahra Municipality and nearby suburbs recall fascinating incidents, people or institutions from their lives/ed., by Robin Brampton. Sydney, WMC, 1998

Jones, Terry and Carruthers, Steven A Parting shot : shelling of Australia by Japanese submarines, 1942 Sydney, Casper, 2013

Marinato, Vincent The Shop on the wharf : recollections of people and happenings in Watsons Bay during the first seven decades of the twentieth century. Sydney, Wild & Woolley, 1996

Footnotes

i An account of Reginald Thornton’s actions on 7-8 June 1942, supplied by his son Graham in an interview 18.3.2010, in Jones, Terry and Carruthers, Steven A Parting shot : shelling of Australia by Japanese submarines, 1942 Sydney, Casper, 2013 p. 33

ii The HMAS Kuttabul, a former harbour ferry requisitioned and converted into a barracks ship for sailors, fell victim to one of two torpedoes released from midget submarine M-24, when Sub Lieutenant Katsuhisa Ban took inaccurate aim at the cruiser USS Chicago. The former ferry was broken in two by the blast unleashed when the torpedo made contact with the harbour floor near Garden Island, where Kuttabul was moored. Aside from 21 dead, at least 10 sailors were injured.

iii Gill, G Hermon Royal Australian Navy, 1942 – 1945. Canberra, AWM, 1968 p. 78

iv Jones, Terry and Carruthers, Steven A Parting shot p. 38

v The motive for the attack on strategically important Diégo-Saurez had been clear and specific – pre-empting Japanese interest, the British had seized the port from Vichy France on 5 May 1942, securing its continuing availability to the Allies. The motive for attacking Sydney was a reconnaissance report of ‘battleships and cruisers’ in the harbour. Gill, G Hermon Royal Australian Navy,1942-1945 pp. 65.

vi The lowest number is derived from early newspaper reports; the highest from David Jenkins’ Battle surface: Japan’s submarine war with Australia 1942-1945, Syd.’ Random House, 1992 p. 251, based on an arguably misunderstood account from Japanese sources. Jenkins’ tally is discussed by Terry Jones and Steven Carruthers in A Parting shot, shelling of Australia by Japanese submarines, 1942 Sydney, Casper, 2013 pp. 147-148.

vii Gill, G Hermon Royal Australian Navy, 1942 – 1945. Canberra, AWM, 1968 pp. 77- 78

viii Jones, Terry and Carruthers, Steven A Parting shot pp. 189-190.

ixOp.cit. p. 209

x In 1945, Mochitsura had been the Commander of the I-58 which had torpedoed and sunk the USS Indianapolis. Terry Jones and Steven Carruthers drew from the transcript of his evidence into a post-war inquiry into the sinking to gain insight into Japanese submarine operations A Parting shot pp. 209f

xiOp. cit pp.209-210

xii Op.cit pp.260-261

xiii Gill, G Hermon Royal Australian Navy, pp. 64f

xiv Jones, Terry and Carruthers, Steven A Parting shot p. 258

xv Gill, G Hermon Royal Australian Navy, 1939 – 1942. Canb., AWM, 1957 p. 643

xviOp.cit. quoted by Jones and Carruthers p. 51