The foreshores and adjoining landscape of Keltie and Blackburn Coves – Diendagulla to the Cadigal people, traditional owners of the land – once teemed with wildlife, supported by the natural vegetation of the area. In the nineteenth-century, the Double Bay locality, a low-lying swampland draining run-off from the surrounding hills, was to prove remarkably fertile ground for the agricultural and horticultural enterprise of early European settlers.

The land’s potential was recognised by the colony’s first official botanist, Charles Frazer, who recommended the area to Governor Macquarie as the site of a second Botanic Garden, a plan which failed to eventuate under Macquarie’s successor. Nevertheless, within a few decades of Macquarie’s 1821 departure, the alluvial flats at Double Bay had come to support extensive market garden activity, and several well-considered nurseries – one of particular renown.

Beyond this commercial use of the land, the area was distinguished in the nineteenth-century by a number of landmark private gardens attached to the houses of the colonial gentry, famous attractions in an era when the pursuit of horticulture had become a mark of status, and the importing of exotic plants was much in vogue.

Through nineteenth-century eyes

The natural topography and plant life of Double Bay, which would be fundamentally altered by its eventual urbanisation, was still part of living memory in the mid-twentieth century. Members of the long-resident Surridge family of Double Bay, brothers James and Arthur, recalled the area for James Jervis in his centenary history of Woollahra. The two brothers spoke of mangroves growing on the mudflats where the Hugh Latimer Centre now stands at the eastern end of William Street1 - in an era when boats could be rowed up to the western end of William Street via a lagoon, later tamed through land reclamation and storm water systems.

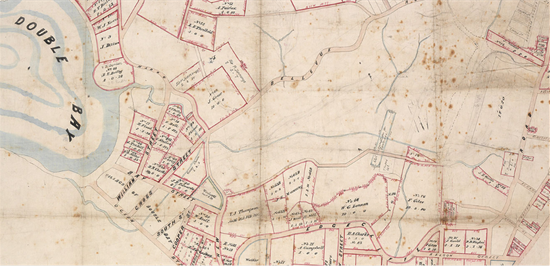

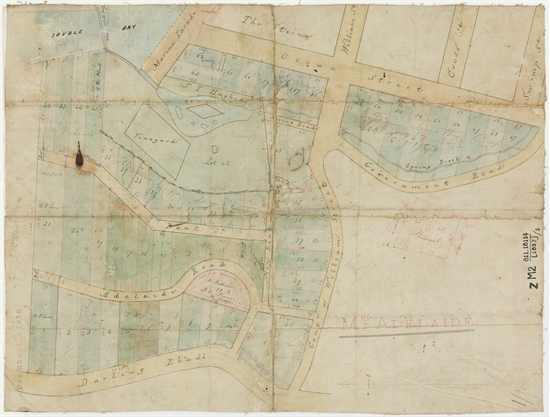

The network of streams descending to the Double Bay Creek on the floor of the valley between Edgecliff and Bellevue Roads, are shown on this 1850s map, as well as the streams entering at each end of the Keltie Cove beach. On the higher ground the beginnings of development is represented in records of the leaseholds issued from the Point Piper estate as suitable building sites. Extract from map - ‘Point Piper estate’ c1855 SL NSW - M Z/M4 811.1812/1855/1

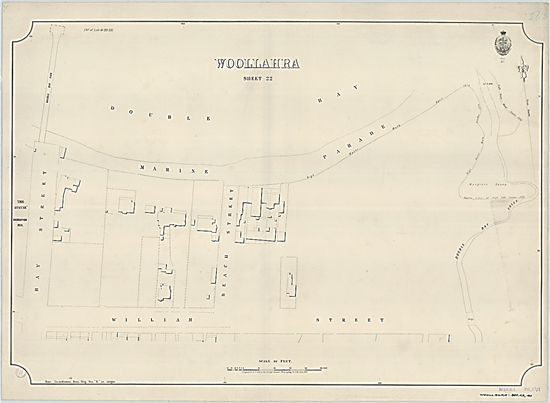

Sydney Metropolitan Detail Series, Woollahra Sheet 22, 1889/ NSW Surveyor General’s Office. SLNSW - M Series 4 811.17/1

The natural course of the Double Bay Creek is shown on the right of this plan, and an area of Mangrove Swamp marked centre right. A bridge at its eastern end carries William Street across the creek. The eventual site of the Hugh Latimer Centre, built in the 1950s and cited by the Surridge brothers in 1960 as occupying the former mangrove line, lies north of the bridge.

View of Foster Park and the Hugh Latimer Centre, 1970s. Woollahra Digital Archive PF006360/0174. The low ground surrounding the Hugh Latimer Centre is reclaimed mangrove swamp. The fence line visible beyond the parked cars follows the covered channel containing the Double Bay Creek.

The route to South Head remembered

In the 1920s, James Arthur Dowling, an early and active member of the Royal Australian Historical Society, presented a paper to the RAHS based on his youthful memories of the landscape followed by New South Head Road. The son of Judge Dowling of the District Court, Arthur had been raised at Brougham, his family’s home from 1863, and set his reminiscences for the Society in that decade.

Brougham, home of Judge James Sheen Dowling, cnr Wallis and Nelson Streets Woollahra. Woollahra Digital Archive PF004103

While Dowling singled out no individual plant species by name as specific to the Double Bay locality, he provided a detailed view of the topography and natural features which determined the native flora of the area. Dowling describes the watercourse – once known as the Double Bay Creek - which fed the area, and the Edgecliff Gully at the head of Double Bay which centred on this stream, referring to the dense covering of bushland on the higher ground.2

The whole of Bellevue Hill, with the exception of a few dwellings abutting on or overlooking Double and Rose Bays, was covered with dense bush. Between this hill and the southwest portions of Woollahra, was and is now a large depression or valley, known as the Woollahra or Double Bay Gully, which commenced near the junction of Woollahra and Waverley on the east, and extended to the waters of Double Bay.

Running through was a natural stream which collected and conveyed the flow of storm-waters from the surrounding high lands into the bay. This natural stream of waterway – near “Glenyarrah”3 – has since been converted in to a modern water channel collecting and discharging the waters more effectually into the Bay. This gully was the resort and happy hunting and playing ground of the youths of the neighbourhood – I being one of them.

(Dowling, Arthur Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society

Vol X, 1924 p. 47)

‘View of Double Bay, Sydney Harbour’, c1879. Nicholas Caire Anglo-Australasian Photo company. Woollahra Digital Archive PF004730. The heavily timbered hills above the bay, described by Arthur Dowling, are shown in this nineteenth-century image. In the foreground, the lagoon at the western end of the Keltie Cove beachfront can be seen entering the bay, and at the far end of the crescent of sand, the main Double Bay Creek discharges in its natural form among rocks. Buildings on the Glenyarrah (Gladswood) property are visible amongst the trees above.

Zamia, ti-tree and ferns

Elsewhere in his paper, Dowling speaks of the pleasures of long recreational walks with his father, setting out from Brougham to either the city or the South Head, their enjoyment enhanced by their pleasure in a bushland ‘interspersed with innumerable plants of zamia or black fellow’s potato, with their long-stemmed flowers, and flowering shrubs.’4

…in addition to the constant exquisite views of the harbour, the landscape was covered with a profuse growth of trees, zamias, native flowers, and all descriptions of ferns. Now all this wild state of the country has entirely disappeared, and both roads are fringed with buildings almost to South Head, with modern gardens on both sides…

(Dowling, Arthur Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society

Vol X, 1924 pp. 54-55)

In describing the country around Rose Bay, Dowling notes the preponderance of Ti-tree scrub, sought after by later suburban dwellers as thatching for their garden bush houses, just as the peaty soil of the swamplands was prized as an additive to enrich their gardens.5

By ‘zamia’, Dowling meant the cycad macrozamia communis, also known as the ‘Burrawang’, endemic to eastern New South Wales and the most southerly occurring cycad in the world. The large seeds of the plant, provided they are liberally washed under running water to remove toxins, are a useful food source.

Being typical occurrences within Sydney’s coastal bushland, it is likely that zamia and ti-tree would also have been found in neighbouring Double Bay.

Ti-tree (leptospermum) in flower.

A mature Burrawang plant.

The partially depleted 'fruit' of the Burrawang – the cluster of seeds initially encased within a green cone, and the pale kernels glimpsed through the fleshy red encasing which is breaking down.

‘Toothsome delicacies’ of the bush

More explicit detail on the flora of Double Bay comes from a columnist in the Herald, identified only as ‘E.S.’, who wrote in 1904 of the Double Bay he had known fifty years earlier.

According to his account, youth would walk from the city to collect the berry-like fruits of the ‘Geebung’ (persoonia lancolata) and ‘Five corners’ (styphelia incarnate) – shrubby trees which grew in abundance amidst the natural bushland around Double Bay and Rose Bay, due to a tolerance for sandy soil. Each fruit of the ‘Five corners’ plant was housed in an arrangement of five sepals, the shape of which gave the fruit, and plant, its colloquial name. ‘Geebung’ or ‘Geebong’ was the European approximation of the indigenous name for both fruit and plant.

E.S. wrote that ‘gees and fives’, as they were known for short, were ‘to the lads of long ago …a toothsome delicacy’. Moreover, there was a sale for the native fruit in the George Street markets (1 penny for a wine-glassful) – and the lads who gathered the fruits around Double Bay were sometimes robbed of their bounty at Rushcutters Bay, where gangs known as ‘The Forties’ would lie in wait.6

Earlier, throughout coastal Sydney, these same fruits had been part of the diet of the traditional owners of the land. Colleen Morris writes of ‘The Great Lost Garden’ in her 2008 book, Lost gardens of Sydney, noting the vital significance of the foreshore land to Aboriginal people:

‘The coastal swamps supplemented their principle food supply of fish, shellfish, and meat with edible roots and tubers. The heaths and the shrublands provided small fruits such as those of the geebung’… and they used nectar from the flower spikes of banksias and the grass tree (Xanthorrhoea). White settlement soon displaced them from this horticultural Eden’

(Morris, Colleen Lost gardens of Sydney p. 12).

A disappearing landscape

Like Dowling, writer E.S. before him wrote of a wealth of wildflowers that grew in the environs of the three adjoining bays east of the City - Rushcutters, Double and Rose - referring by name to Boronias, Epacrids [sic] and Christmas Bush.7 Some of the flower-bearing shrubs of the locality would be adopted as cultivated garden plants in the suburban period that was about to supplant the innate.

Early photographs and paintings of the Double Bay locality confirm the texts which described the landscape – the hills appearing as heavily timbered with eucalypts predominating, and any yet uncleared ground in the lower-lying areas supporting low-growing scrub-like vegetation. However, work to prepare the lower ground for agriculture was underway by the mid-nineteenth century, so the surviving visual record of the uncleared swamplands is sparse.

What might have been – The Botanic Gardens of Double Bay

In 1821, Governor Macquarie and various senior officials investigated and surveyed land at Double Bay as the site of a Botanic Garden, proposed as an addition to the older ‘Government garden’ at Farm Cove, which Macquarie had dedicated as a Botanic garden in 1816.

Macquarie’s journal entry for Tuesday 4th September 1821 records the outcome of a trip to Double Bay, which led to the identification of a site for the future garden and the Governor’s order that the land be measured and set aside for this use.

Thursday 4 Septr.

I went by Water this forenoon, accompanied by Mr. Meehan Dy. Surveyor Genl., Mr. Chas. Frazer Colonial Botanist, Capt. Piper and Lieut. Macquarie – to Double Bay, and there marked the future Botanic Garden, directing about Twenty acres of Ground to be reserved & located for that purpose.

(Macquarie, Lachlan Diary 11 March 1821 - 12 February 1822)

Charles Frazer, appointed the superintendent of the first Botanic Gardens at the time of their dedication in June 1816, is considered to have been, five years later, the driving force behind this reservation of land at Double Bay. The area selected was to the south of the Keltie Bay shoreline, the rich alluvial soils and small watercourses of this area no doubt a decisive factor.

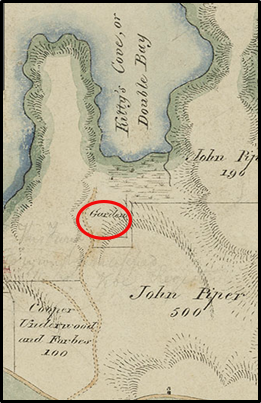

The location of the garden is indicated on a map of the Parish of Alexandria held in the State Library collections. Drawn in 1841, twenty years after Macquarie’s visit to Double Bay, the map is the work of emancipist Peter Lewis Bemi, a former government draughtsman and surveyor by then operating privately.8 Bemi’s plan is presumably derivative, as this map reference to the once proposed Botanic Garden was long outdated by the time of its drafting.

Extract from Peter Lewis Bemi’s Map of the Parish of Alexandria 1841. SL NSW ZM2 811.181 1841 1 indicating the site of the proposed Botanic Garden

Charles Frazer clearly enjoyed the confidence of Governor Macquarie. His unofficial patron, however, departed New South Wales in February 1822, before anything further would be done towards creating the Double Bay Botanic garden. Macquarie’s successor, Governor Brisbane, did not proceed with the plan – although he did add another five acres to the Farm Cove garden, possibly by way of compensation.9

From planned garden to suburbia

The reserved area at Double Bay was re-surveyed by Surveyor Larmer in the 1830s, and became a crown land release, styled as ‘The Village of Double Bay’. Thirty years after Macquarie’s visit, a small portion of this area would be home to Michael Guilfoyle’s Exotic Nursery, a land use coincidentally appropriate in terms of Charles Frazer’s 1820s vision. Today, the area is associated with retail and business as well as supporting important community facilities such as the Double Bay Public School and the Steyne Park.(PDF, 344KB)

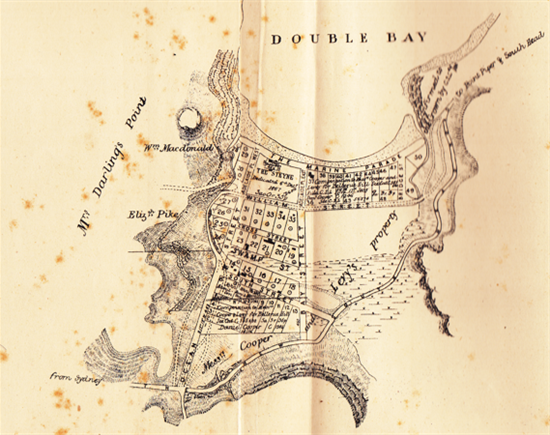

Plan of the Village of Double Bay, Crown land subdivision surveyed 1834. Plan laid before the Executive Council 2 August 1834, reproduced with annotations in Double Bay correspondence 1878-9 ordered by the Legislative Assembly to be printed April 1879 (Parliament of NSW) Appendix I.

Historian Rosemary Broomham in her Thematic history of Double Bay, comments on the mid-nineteenth century Bay locality:

In spite of the concept that Double Bay began as a fishing village, market gardeners and nurserymen were more numerous than fishermen in the 1850s and 1860s.

(Rosemary Broomham, Thematic History of Double Bay p. 11).

While some of these gardeners were attached to the great houses, Broomham was writing of the market gardeners who made a living from the soil leased from the Cooper estate. The first of these gardeners were European, but in time they were joined, and eventually outnumbered, by a community of Chinese gardeners, who settled in the district in the last decades of the nineteenth century.

A perfect topography

The low-lying swampland at Double Bay was excellently suited to agriculture – and market gardens also flourished in the similar terrain around Rushcutters Bay and Rose Bay.

The Reverend Canon Wilson in a descriptive article published in the Illustrated Sydney News in 1889, writes of the land at the head of Double Bay as ‘an immense alluvial flat, cut in two by the perennial creek meandering through its centre’. Water was in plentiful and reliable supply, and the soil properties ideal for intensive cultivation:

The rich, black, unctuous soil delighted the heart of the market gardener, and pretty well for a whole generation these lonely solitudes were devoted to the growing of cabbages.

(Canon Wilson, Illustrated Sydney News p. 11)

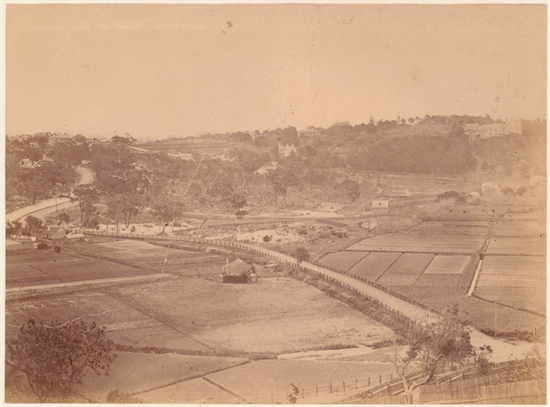

View of the market gardens at Double Bay. Small Picture File collection, Mitchell Library SL NSW - [c1875-1885] SPF / 651

Courtesy of the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. The photograph is taken from an elevated position on Bellevue Hill, looking north-west along New South Head Road. The roads visible in the foreground are Bellevue Road (branching southwards to the left) and the Cross Street intersection, far right. To the west (left of image) New South Head Road climbs to the Edgecliff ridge. The prominent house on the hillside (right side of image) is Greenoakes, perched above Ocean Avenue.

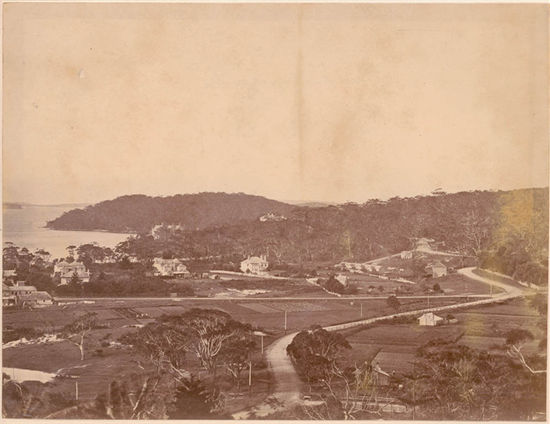

View of the market gardens at Double Bay. Small Picture File collection, Mitchell Library SL NSW - [c1875-1885] SPF / 650

Courtesy of the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. The photograph is taken from an elevated positon on the Edgecliff Ridge, looking south-eastwards along New South Head Road – the main road of the locality. The road visible in the foreground branching from New South Head Road is Manning Road. Cross Street bisects the mid-ground, and the two main houses beyond it (Cadaxton and Lowlands) front William Street, the steep gradient of its intersection with the main road visible at right. In the distance, the rooflines of Glenyarrah/ Gladswood and Redleaf are visible – Gladswood above the shoreline and Redleaf on the hillside, mid-picture.

The market gardens of the Bay have been illustrated in a number of visual sources, and two photographs held in the collection of the Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, show clearly the patchwork of allotments bearing different vegetable crops. These views indicate that by the mid-1870s, the lower reaches of the Double Bay Creek were regulated within a man-made canal system, part of the remedial work of the gardeners, as they maximised the productivity of the land.

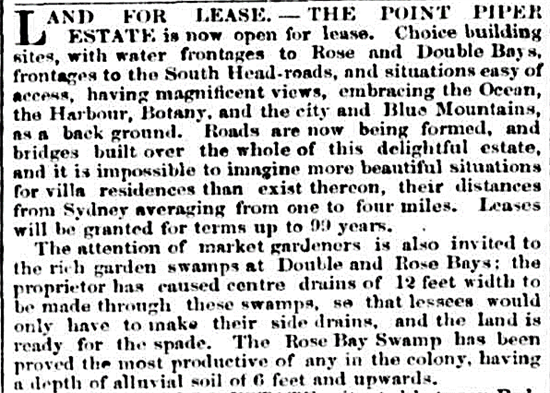

This was foreshadowed by an 1856 advertisement, aimed at market gardeners, for Cooper estate leaseholds.

The attention of market gardeners is also invited to the rich garden swamps of Double and Rose Bays: the proprietor has cause centre drains of 12 feet width to be made through these swamps, so that lessees would only have to make their side drains, and the land is ready for the spade

(Sydney Morning Herald 29 January 1856 p.8)

The lands of the Point Piper estate opened for leasehold after the death in London in 1853 of Daniel Cooper, the terms of whose will proscribed sales for a determined period. Sydney Morning Herald 29 January 1856 p.8

The 1870s images of the market gardens landscape also bear out the account of James and Arthur Surridge, who recalled that the land under cultivation by market gardeners – defined by the brothers as the area from Manning to Bellevue Road, and on both sides of New South Head Road – lay ‘six or seven feet below the roadway’.10

The embankment which carried the elevated roadway is visible particularly in the image of the market gardens from Bellevue Hill (SPF 651), and provides an indication of the extent of remediation required before this land could be given over to residential development in the early twentieth century.

An asset becomes a liability – the consequences of flooding

The poor drainage of the low lying ground could spell disaster for the gardeners in times of freak rainfall, as occurred in April 1887 when the Herald reported that the Double Bay market gardens were ‘entirely under water’, and the watercourse ‘running a perfect cataract’ – in an instance when the plentiful supply of water proved a catastrophic disadvantage.11 This was by no means a singular event, as other newspaper accounts at different times throughout the market garden era indicate.

Nevertheless, the benefits were seen to outweigh these occasional harmful consequences, and cultivation followed the course of the creek southwards through the variously named Double Bay or Edgecliff gully, with the area of the present-day Lough playing fields also home to cultivation and dairying.

Operation of the market gardens in Double Bay followed a pattern typical throughout New South Wales, in being pioneered by Europeans and eventually taken up by Chinese labourers and lessees.

The first issue published of the Sands Sydney Directory, compiled for the period 1858-1859, lists the names of two men identifiable as market gardeners in Double Bay – Robert Blackburn and William Brett. It is possible these were the earliest in a line of gardeners which worked this land for decades, although market gardeners had been active in the neighbouring Rushcutters Bay valley, on the Booth estate (eventually the White City lawn tennis complex) from the 1840s.

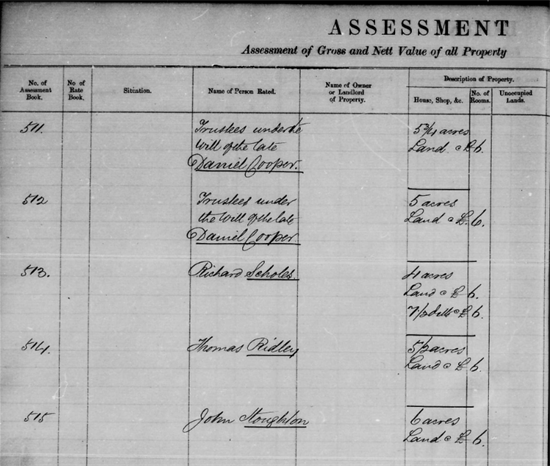

Among the mid-nineteenth century European gardeners of the Bay was John Houghton, established in the area from the 1860s, if not earlier. Houghton’s enterprise was of sufficient scale and prosperity to generate employment, at least seasonally, demonstrated in advertisements for labour in the press. His success appears to have eventually allowed him to diversify his interests as time went by – commensurately reducing his involvement in market gardening.

A similar pattern is told through Thomas Ridley’s story – gardening first at Rushcutters’s Bay in the 1850s and expanding those interests into the neighbouring Double Bay gardens area in the 1860s. At the same time, Ridley also acquired and operated a stone quarry, on the higher ground above the Bay, at the junction of Edgecliff and New South Head Roads, and as part of this land was spent of its worthwhile materials, Ridley built a hotel – The Richmond - on the site, of which he was proprietor. As an assisted immigrant from Ireland who brought with him agrarian skills, Thomas Ridley showed a readiness to seize opportunities and take them in various directions.12 Marketing gardening, however, appears to have given him his start.

This page from a microfilm copy of the first Assessment of Woollahra Council, compiled in 1860, shows the names of three Cooper estate leaseholders related to Double Bay’s history of agriculture: Richard Scholes, Thomas Ridley and John Houghton.

New gardeners, new ways

In the case of John Houghton - when the 1885 issue of the Sands Sydney Directory was published, he was no longer listed, as he had been for years before, at a garden on the southern side of New South Head Road, and nor does the occupation ‘market gardener’ appear next to his name in the listing for him as a householder in Cross Street, Double Bay. In the place of his name on the New South Head Road frontage is the name Sum Cue, and when the 1890 issue of the directory was compiled, Sum Cue’s name had been joined by the names Lee Chong, Foon Ah and Sung Yong.

This was a story frequently repeated, and a trend which saw the industry increasingly adopted by Chinese immigrants, especially as confidence in gold mining, which had brought many Chinese to Australia in the mid-nineteenth century, fell away with the end of the ‘gold-rush’ boom. It has been remarked that, ‘By the end of the 19th century, these labour intensive farms [market gardens] had become almost synonymous with the Chinese.’13

Extract from map - ‘Point Piper estate’ c1855. SL NSW - M Z/M4 811.1812/1855/1. Gooy Chum’s irregularly shaped land parcel of almost 2½ acres was later developed as the Knox Street locality.

This shift in tenure and labour was evident also in Double Bay. The development was demonstrated in the evolving language of newspaper articles when describing the local district. In the 1870s and early 1880s, writers spoke of the ‘market gardens’ of Double Bay, but by the later 1880s, the collective reference was to ‘the Chinamen’s gardens’ of the locality.

It is unknown whether this transition in the Double Bay holdings met with resistance among the established local European growers, since accounts specific to the area have not been traced. Within the industry overall, resentment of the market share taken by the Chinese, suspicion of their trading practices, and scepticism about the introduction of previously unused farming methods was widespread.

There is no doubt however, that the broader community around Double Bay was not immune from racial tensions noted elsewhere. In charging John Reid, a clerk of Woollahra, for throwing a stone which struck Yee War, a Double Bay market gardener, in an unprovoked attack upon the plaintiff as he stood on his own veranda, magistrate Mr Isaacs remarked that,

‘He had himself repeatedly seen those Chinamen attacked by boys throwing stones at them, and had even chased boys himself, but could not catch them’

(Evening News 15 July 1898 p. 2).

The crops of the local gardens

No comprehensive list of the vegetable crops grown at Double Bay has been traced. We do know that French beans were grown by at least one gardener in the Double Bay district, due to the documented theft of two bushels of the same from the Double Bay garden of Sun Bee Hing in 1903.14 In the absence of other specific information it would seem safe to assume that crop selection would have matched the known choices made elsewhere by market gardeners farming in comparable conditions, and would have remained relatively unchanged over the decades. The Chinese may have taken a different approach to various aspects of the exercise, leaning towards collaborative efforts in both growing and marketing, and introducing techniques such as crop rotation and double cropping. However it is unlikely, given their demonstrated business sense, that they would have deviated from the Eurocentric range of produce which was known to have an established local market.

A report published in an 1898 regional newspaper provides insight into appetites both local and further afield. Discussing the trade in vegetables, both inter-colonial and for overseas export, it was noted that pumpkins, carrots, parsnips and cucumbers were sent from New South Wales to Victoria, while cabbages, swede turnips and carrots were despatched to Brisbane and New Caledonia. Meanwhile, cauliflower and onions were imported to Sydney from Victoria, to supplement local varieties which, it was suggested, were inferior for being ‘quickly-forced Mongolian products’ grown at Botany, Paddington, Waterloo and Waverley.15 It would seem unlikely that the gardeners at Double Bay would have strayed far from the staple crops cited.

The decline of the market gardens in Double Bay

Market gardening was eventually forced out of Double Bay by increased land values and the associated impetus for development. Cottages and bungalows spread along the route of New South Head Road, eventually giving way in turn to retail business and service industry. An 1887 harbinger is the report of ‘a fine terrace of houses’ in progress of erection ‘opposite Ferguson’s nursery’16 – a reference to a building underway on the northern side of New South Head Road, east of Gum Tree Lane. The Ferguson’s enterprise in itself represented change, in that this business, catering to interest in ornamental plantings rather than practical sustenance, had taken up former market garden land.

An agricultural presence persisted into the first decades of the twentieth century, contracting away from the main arterial road and into the valley to its south. In 1907 there remained nine separate leaseholds for market gardening in the Edgecliff Gully, according to council assessment records, some of which parcels converted to freehold. However, the activities of dairying and gardening would prove at odds with urban development, both economically and socially, as a more suburban mentality evolved. Council resumed some of these lands for open space provisions,17 while private subdivision and building activity completed the purge of this way of life.

Not all the commercial gardening pursued at Double Bay involved staple produce for the table. Landscapers and nurserymen also came to occupy a firm niche in the locality, existing amidst the market gardens and the gardens of a clientele which - above and beyond well-resourced kitchen gardens and orchards - typically cultivated for aesthetic pleasure, personal interest and the honour of possessing rare horticultural specimens.

There was a pattern among the nurserymen of Double Bay for their retail enterprise to have grown out of working relationships forged with the owners of landmark gardens situated nearby. Michael Guilfoyle’s local start – after a failed nursery enterprise at Redfern – came from his association with Thomas Sutcliff Mort, after a chance meeting c1849/50 through shared horticultural interests. Mort gave Guilfoyle the task of creating the gardens of his newly-built Greenoakes, and the use of the Double Bay land on which Guilfoyle established his famous Exotic Nursery, an association marked today by the street-name Guilfoyle Avenue.

George Mortimore

In Guilfoyle’s footsteps came George Mortimore, Mort’s gardener from the mid-1860s, and a nurseryman of Cross Street, Double Bay from 1874. Mortimore was an influential figure in Sydney’s horticultural spheres, regularly exhibiting and presenting papers to fellow enthusiasts though the several Horticultural Societies, and sharing his knowledge with the broader public through lectures at the Sydney School of Arts. He was also an active advocate and commenter in the mainstream press regarding all things horticultural, especially through his letters to the editors of the Sydney dailies.

In 1877, Mortimore took charge of the Horticultural section in the Sydney-based Intercolonial Exhibition, and in 1888 was steward of the ‘Floral Annexe’ of the Women’s Exhibition at the Centenary Fair held in the Intercolonial Exhibition Building at Prince Albert Park Redfern in October, as the closing event of Centenary celebrations.18 Mortimore is at times referred to as a ‘florist’ in some of the newspaper coverage of his work, and it would seem he had high level skills in presenting floral displays, as this account of the ‘Floral Annexe’ conveys:

The floral annexe is the first object which strikes the visitor on entering the main building, and is a large structure 50ft x 30ft, with a high arched roof. Here the plants and flowers brought in for competition have been arranged in tiers, and with due regard to the harmony of colours

(Evening News 3 October 1888 p. 5)

Mortimore was not only a visible public figure on the subject of gardening, but also accomplished in his trade, consistently winning prizes and accolades for the specimens he exhibited. There are multiple references to his repeated success in the Sydney Morning Herald, the Australian Town and Country Journal and the Evening News between 1866 and 1890.

Unlike fellow nurserymen Michael Guilfoyle, John Gelding and John Ferguson, who moved or divided their nursery businesses across the city, the Devonshire-born George Mortimore remained fixed within the Eastern Suburbs, dying at his Hargrave Street home in Paddington in January 1890.19

John Gelding

John Gelding followed the same trajectory as Guilfoyle and Mortimore - from head gardener to nurseryman – benefitting from a successful connection with the largest landholder in the district, Sir Daniel Cooper. Gelding was appointed the overseer of the Cooper estate in 1853, and occupied the position for almost eight years. He was responsible for the gardens at Rose Bay Lodge, which was at that time the Cooper family’s home, and also for work on the grounds at Point Piper, where in 1856, Cooper had, with much ceremony, laid the foundation stone for his Woollahra House.

Gelding’s work for Cooper, taken with earlier Australian commissions for prominent property-owners (Cowper’s Wivenhoe and Macleay’s Elizabeth Bay House) and overlaying respected qualifications and experience earned in England, stood him in good stead when, in 1861, Cooper’s permanent return to England brought both the need and the opportunity for change.

Gelding entered into partnership with his brother and fellow horticulturalist William, and as Messrs J & W Gelding they founded a nursery business. Initially opening at Rushcutters Bay, the brothers moved shortly afterwards to Cross Street in Double Bay, and established a related outlet at the city markets selling seeds and flowers. In both areas the Gelding brothers created a flourishing business.

The nursery was moved in 1869 to Petersham, but only when the enterprise outgrew the Double Bay site, while the city presence was maintained long term. The expansion – onto a site of 12 acres off Canterbury Road – was well managed, and with John Gelding’s death in 1900, he left a steady business on sure foundations to be carried on by descendants.20

John Gelding – portrait published March 1900. The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser

Gelding’s influence in the horticultural sphere increased as he aged. Always active in the Horticultural Society, he served as President in the early 1880s, and also took up writing on the subject – as editor for Horticultural magazine and as a contributor on horticultural matters for the Sydney Mail. It has been commented that these writings are Gelding’s greatest legacy.21 His death in 1900 drew a number of obituaries in the Sydney press, and an account of his funeral indicates a strong representation of the horticultural world of Sydney.22

Gelding’s period in Double Bay, though short, is significant, given the impact of his work and contribution on colonial thinking in his field.

Francis Ferguson’s Australian Nursery

As with the nurseries of Gelding, Guilfoyle and Mortimore, the founding of The Australian Nursery, which operated a branch in Double Bay from c1878, had its genesis in the relationship between founder, Francis Ferguson, and one of the great colonial estates of New South Wales - the Macarthur family’s Camden Park. Ferguson, immigrating in 1849, found employment at this large pastoral estate west of Sydney, a legacy of pioneers John and Elizabeth Macarthur, by then under the wise stewardship of their sons, William and James.

William Macarthur (later Sir William) was an erudite botanist and trained viticulturist who had also a keen interest in all aspects of horticulture. By the early 1840s he was already importing European plants, not only to enhance the gardens associated with his family’s 1835 John Verge residence, but to experiment with plant raising, breeding and sales. By the end of the decade, Camden Park was sending supplies to nurseries and professional growers in four colonies, and the property was amassing a collection of plants and fruits which would be acknowledged in 1864 by visiting expert John Gould Veitch as ‘by far the best I have seen in the colony.’23 There could have been no better local grounding for Francis Ferguson’s own enterprise, which was established in the 1850s.

As a tenant of the Camden Park estate, and with a view of its main house from his nursery, Ferguson maintained a good relationship with his former employer24 and it would seem, close ties – with one historian observing that he attended to sales on Sir William Macarthur’s behalf during Macarthur’s absence from Australia.25 Ferguson’s Camden nursery flourished and expanded, opening for a time a ‘depot’ at Campbelltown, and eventually, seeking a ‘metropolitan’ outlet - in an era when Camden was considered distinct from Sydney. This need was filled with the opening of a branch nursery at Double Bay.

The nursery business at Double Bay, where Messrs Francis Ferguson & Sons opened in 1878, was run by Francis George Ferguson’s eldest son, Francis John Ferguson. Born in Camden in 1852, Francis had married Anne Henrietta Watson in 1875, and a daughter, Margaret Elizabeth (Lizzie) had been born in the Campbelltown district in 1876.26 The family now relocated to a house on the southern side of Cross Street, between the Bay and Ocean Street intersections, where in July 1880, a son was born.27 However, by 1885, the family home Braemar, had been built on the nursery property, house and nursery sited on 4½ acres of ground on the southern side of New South Head Road, to the north-east of the Manning Street intersection, former market garden land.

It was remarked in an 1880 newspaper article about his father’s Camden nursery, that Francis Ferguson junior, then at Double Bay, had earlier spent five years ‘in most of the first horticultural houses in England and France’ to further his knowledge of the nursery trade.28 A later newspaper article spoke of time spent training in the London establishment of Messrs Veitch to round off his early training under his father.29 A review of the nursery in 1883 suggests a well-run establishment catering to a discerning public. The report spoke of grounds laid out in a ‘most systematic manner’ and greenhouses ‘filled with the choicest varieties of the floral world, testifying to the taste and care of the proprietors in the management of their stock’. The breadth of selection was also singled out for comment.30

Four years later, reviewed again for the ‘Nurseries of the colony’ series published in the Sydney Mail, Ferguson’s Double Bay nursery once more met with the approval of the reviewer, who was impressed with the hardiness of the stock, surviving in good condition despite a difficult season Sydney-wide. Again the careful arrangement of the nursery – traversed by broad grass walks in a grid dividing stock into types – was a feature of note.31

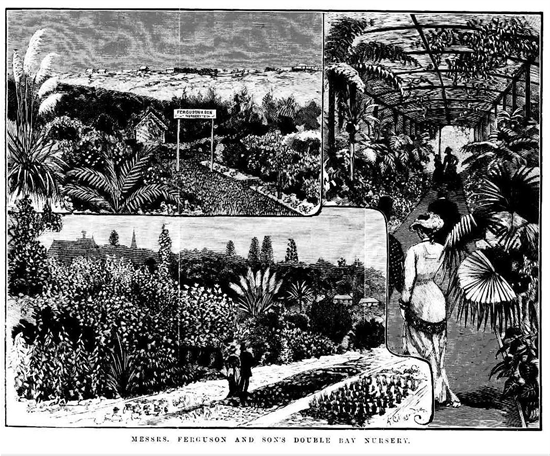

Illustration of Ferguson’s Nursery in Double Bay accompanying an article in the Illustrated Sydney News published 14 April 1883, p. 17.

On 11th July 1899, Francis John Ferguson died at Braemar. Aged 48, he had survived his longer-living father by only seven years. The nursery remained listed in the Sands Sydney Directory at its New South Head Road site until the issue published for 1905, and Francis’s widow and daughter were clearly still in residence at Braemar in April 1902, when daughter Lizzie Ferguson married Alfred Denison Little at All Saints Woollahra, with a small gathering of close friends quietly entertained at Braemar afterwards.32

Lizzie Ferguson’s husband Alfred was to take on a leading role in management of the Ferguson family’s Australian Nursery, becoming a partner in the firm. The birth of the couple’s only son, Sidney F Little, at Camden in 1903, combined with the disappearance of entries in the Sands Directory for the Double Bay nursery after 1904, suggests that Lizzie and Alfred had installed their household in Camden, presumably for proximity to the original Ferguson business, and closed the Double Bay outlet.

The occupation of Braemar by Charles Waller in 1905 would seem to confirm the Ferguson’s complete relinquishment of the Double Bay nursery property, ending an association of over twenty-five years between the Ferguson nursery business and Double Bay.

Michael Guilfoyle’s Exotic Nursery

Of all the well-respected nurserymen of the Double Bay district, the name which stands above all is that of Guilfoyle, partly because of the achievements of the founder of the Exotic Nursery, Michael Guilfoyle, but also due to local pride in his son William’s career, which made the name a household one further afield. Sole among the local nurserymen, the Guilfoyle’s family name is commemorated in a street which indicates the locality of an enterprise which became a local institution.

As with many of the nurserymen of the district, Michael Guilfoyle arrived in the colony with an established career in horticulture and landscaping. With horticultural expertise in the genes of both sides of his family, he had trained in England under Joseph King and James Veitch, and gained the credentials of employment at London’s Royal Exotic Nursery. He also had a number of worthwhile British landscaping commissions to cite by way of introduction when he left England aboard the Steadfast in 1849.33 Nevertheless, Guilfoyle struggled in his first Sydney venture, a nursery in Redfern, hampered by both a lack of local knowledge and a dearth of reliable labour.

Meeting Thomas Sutcliff Mort through the Horticultural Society was a piece of good fortune for both men, and brought Guilfoyle to Double Bay c1851, to attend to the lay-out of the grounds of Mort’s Greenoakes, and to establish the Exotic Nursery – named in honour of the Chelsea establishment. The site for Guilfoyle’s nursery was provided by Mort - 3½ acres of well-watered land on the north-eastern side of the later suburb, on part of the Crown’s ‘Village of Double Bay’, released in the 1830s. Guilfoyle and his family lived in a Mort-owned house which still stands on the corner of Ocean and South Avenues.

The Guilfoyle Family home, cnr South and Ocean Avenues. Photographed by David Sheedy c1960. Woollahra Digital Archive PF005147a

Guilfoyle now found himself operating within a locale highly suited to his expertise, where his horticultural knowledge and design skills were recognised and highly respected. Under his management, Guilfoyle’s Exotic Nursery became widely known for the importing and propagation of many exotic and rare species, for which his local clientele had both an appetite and the means to support. His supplies were also sourced from further afield, including, in its formative stages, the trustees of the Adelaide Botanic Garden.

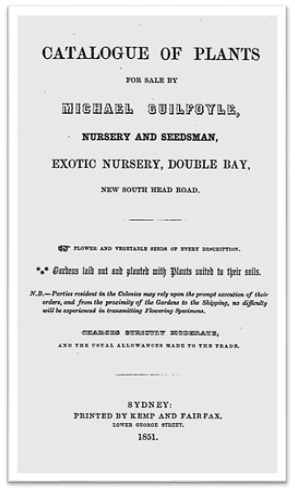

Cover of an early catalogue issued by the Exotic Nursery. State Library of Victoria

Michael Guilfoyle has been credited with introducing both the camellia and the jacaranda to Australia, although the truth is perhaps more complex and more difficult to establish. It is today broadly accepted that the first camellias in the colony were imported in 1826 by Alexander Macleay, for planting at Elizabeth Bay House, and that this move was followed within a few years by William Macarthur of Camden Park, whose establishment was issuing lists of camellia varieties in the early-to-mid 1840s, before Guilfoyle had even arrived in Sydney. This makes a claim for Guilfoyle’s primary introduction of this species unsustainable.

However, Camelia expert Eben Gowrie Waterhouse records that Guilfoyle rapidly gained an ascendency in the local camellia trade, by using grafting rather than layering as his method of propagation, and thus raising robust stock, which withstood unpredictable local conditions. By the mid-1850s, Michael Guilfoyle was carrying off a large share in the awards on offer for camellia exhibits in various competitions.

Guilfoyle is also known to have bred a number of varieties which can be considered his own. E G Waterhouse quotes from the 1877 catalogue of Victorian firm of Taylor & Sangster which listed a number of camellias described as ‘superior seedlings raised by Michael Guilfoyle’. Waterhouse notes also that a number of those listed in the catalogue had been confirmed closer to home by ‘the late Mr. Mortimore, a well-known gardener’ – and it might have been added, a fellow Double Bay nurseryman, albeit not operating at the same time as Guilfoyle was trading from the Bay. We are also indebted to Mortimore for the charming detail that one of Guilfoyle’s camellias, ‘Tabbs’, was named for his cat.34

There seem also to be competing claims to Guilfoyle’s for the honour of having introduced and acclimatised the Jacaranda mimosifolia, a South American tree now so common in sub-tropical regions of eastern Australia that it is often taken to be a native – a fact that belies the repeated failure of early attempts to establish the tree in Sydney. The fact that a flourishing specimen at Drummoyne House was observed as a notable phenomenon by visiting English horticulturalist John Veitch in 186435 attests to the tree’s comparative rarity in Sydney gardens during the period when Guilfoyle was operating from Double Bay. Even as late as 1876, Messrs Ferguson’s nursery at Camden was reminding its customers by circular that there was ‘no second mature specimen in the colony’ to back up the ‘fine’ established Jacaranda in the Sydney Botanic gardens.36

Guilfoyle appears to have been credited – or perhaps credited himself – with overcoming these early difficulties in propagation. A notice which appeared in the Sydney press in November 1868, after referring to the persistent problems which had ensured the local rarity of the tree, announced that ‘This difficulty has been solved by the well-known firm of Messrs Guilfoyle and sons, Exotic Nursery, Double Bay’.37

A paper on the subject of propagating the Jacaranda, presented to the Horticultural Society of New South Wales soon after this boast was published, makes interesting reading – as much for what is omitted as what is included. The paper was presented by George Mortimore, then the gardener to T S Mort at Greenoakes, who made the following comment in his address:

I am glad to see, by a recent notice in the Sydney Morning Herald, that the difficulty of the propagation had [sic] been overcome, and Jacaranda mimosifolia, instead of being rare and scarce, will now be within the reach of all who love a garden.

(Sydney Morning Herald 3 December 1868 p.2)

However Mortimore (at least as summarised by the press) makes no reference whatsoever to the work of Guilfoyle in solving the problem, and moreover, in speaking of his own success with root grafting the plants, indicated that it pre-dated the recent claim:

I have much pleasure in stating that I propagated plants last year, and have succeeded with every graft this season; so the difficulty was overcome at Greenoakes twelve months since.

(Sydney Morning Herald 3 December 1868 p.2)

Mortimore’s paper to the Society continued to expound on the benefits and disadvantages of the different methods of propagating the Jacaranda – layering, grafting, working from cuttings etc – and perhaps paid understated tribute to Guilfoyle in two allusions. One was to the fact that the Jacaranda at Greenoakes had been successfully grown from a cutting twelve years earlier, which places this achievement within the period when Guilfoyle had been the head gardener at Mort’s property. Also, when speaking of his own successful grafts from that same tree, Mortimore notes that ‘having a fine tree to work on, I have an advantage in this respect’.38

A jacaranda in bloom in Manning Road Double Bay. Photographed by Bruce Crosson 1989. Woollahra Digital Archive PF006102

There is no doubt that Guilfoyle was among the early suppliers and successful propagators of the Jacaranda, and presumably he introduced the tree to the gardens of Greenoakes -by Mortimore’s estimation,c1856. One fine early specimen attributed to him occupied a special place in the outstanding grounds of Sir James Martin’s Clarens at Potts Point - prized by its owner among all his collection of horticultural rarities as ‘the dream tree’. This example was specifically claimed by a descendant of Sir James, interviewed in the 1970s, to have been supplied by Guilfoyle’s Exotic Nursery.39

The Jacanda continued to be a prized addition to the Sydney garden long after these subtly competitive discussions of the late 1860s. Almost a decade late, in 1876, the availability of a stock of seedlings of the Jacaranda mimosifolia was the occasion for a special circular to be released by the Ferguson’s establishment at Camden.40 Of the plentiful examples of thriving Jacaranda in the Woollahra area, no doubt many owe their existence to the work of Michael Guilfoyle, which is no small legacy for the nurseryman to have left behind.

Michael Guilfoyle relocated his nursery to Leichhardt in 1874 – a move which coincided and was perhaps precipitated by the move to Melbourne of his son William. His years at Double Bay had been rewarding ones. Not only did he achieve success and recognition through his life’s work, but he found time for community involvement, and served as an alderman of Woollahra Council for several years.

During Michael Guilfoyle’s time at the Double Bay nursery, he saw the first promising beginnings of his son William’s career – no doubt gratifying for him both as father and mentor. William was a keen botanist and a gifted landscaper, and as well as making his own botanical investigations and experiments, he enjoyed the honour and experience of inclusion in a scientific expedition to the South Seas on the HMS Challenger in 1868. William would be eventually mentored by some of the leading scientific authorities of the day in Sydney and Melbourne, their interest in him proving an early measure of his abilities.

W R Guilfoyle c1888. State Library of Victoria Accession no H2819023

In 1873, William Guilfoyle was appointed curator of the Melbourne Botanic Garden, and in a controversial move designed to balance the scientific with the aesthetically pleasurable, undertook a major landscaping work which, over decades, transformed the garden into its current form. His landscaping eye elevated the institution’s status to an internationally recognised example of the picturesque type – ‘absolutely the most beautiful place’, was the assessment of the visiting Conan Doyle41.

Not ignoring the scientific and educational purpose of the garden, William also developed botanical collections, and managed to make time for private commissions and self-educating travel. He retired in 1909, and died in Melbourne in 1912, survived by his wife and only son, William James Guilfoyle.

Another of Michael Guilfoyle’s sons, John, would also go on to have a horticulturally-based career, eventually taking on the curatorship of the reserves managed by the City of Melbourne, helping to ensure the name Guilfoyle is well-remembered.

The nurserymen of Double Bay made their mark on many enduring features of the landscape both within and beyond the Woollahra area – not only in gardens directly shaped through their associated landscaping work, but in the plants and seed which they distributed in the neighbourhood and exported further afield. On a local level, their presence in the bayside locality was a central part of its economic and social history.

Double Bay was periodically the subject of descriptive articles in the nineteenth century Sydney press, and the gardens of the area were typically highlighted as characteristic of the locality and its residents. ‘Handsome houses, luxuriant gardens and carefully-kept orchards’ wrote the Illustrated Sydney News in 1871, observing the area’s nurtured ‘tropical’ appearance, and referring to the many introduced species, the graceful palms, staghorn and ferns, stately Norfolk Pines, and exotic fruits such as banana and Brazilian cocoa nut plants – by implication evidence of a certain whimsical indulgence on the part of the householders.42

Thomas Sutcliff Mort’s Greenoakes, 11 Greenoaks Avenue Darling Point, photographed in 1991. Woollahra Digital Archive – Register of the National Estate, Woollahra Municipality [images]

This property, which would draw such superlatives, was acquired by Mort in 1846 – a part of the Crown’s release of Darling Point in the early 1830s. The estate was previously held by ironmonger Thomas Woolley, for whom architect J F Hilly had built Percyville on the site in 1841. Mort later enlarged the house, with Edmund Blacket as his architect, and re-named his estate Greenoaks.

Mort was a highly successful merchant and respected member of the colonial society, whose energies and enthusiasms led to wide-ranging interests, both in his personal business affairs but also his public life, his benefaction and his drive to promote the advancement of the colony.

The gardens of Greenoaks were a project which engaged him as greatly as any of his efforts, aided by the gifted landscapers who worked to create his vision, but propelled by his own involvement and knowledge of horticulture. The house and garden survives into the present time - largely intact, though with sympathetic modifications to the house (Leslie Wilkinson as architect in 1935) and some erosion of land area. This preservation came mainly due to institutional ownership, the property having been purchased in 1911 by the Sydney Diocese of the Anglican Church as the official home of its Archbishop.

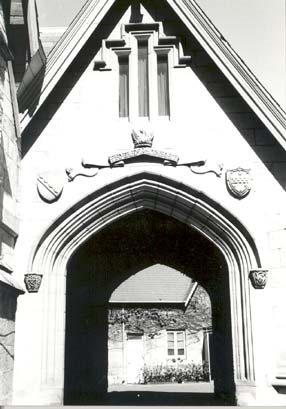

Detail of a covered carriageway within the Greenoakes grounds. Woollahra Digital Archive – PF002226

While Greenoaks is routinely singled out, the 1940s Sydney writer Glynde Nesta Griffiths linked as a triumvirate, Brooksby, Greenoakes and Ecclesbourne, all three perched on land high above the western shore of the bay, and all with gardens ‘tended by hosts of gardeners and full of all sorts of exotic plants supplied from Mr Guilfoyle’s nursery’. Of the 1847 house Brooksby, where the convict-built garden included ornamental lakes fringed by groves of azaleas, Griffiths writes of ‘glorious English trees and shrubs’45 as a structural basis for the horticultural overlay of flowers and shrubs.

The gardens at Brooksby are shown in a series of images in the Library’s Digital Archive, as a place of pleasure for its household with leisure encouraged by a tennis court and places created for quiet enjoyment, the whole enlivened by a resident peacock and wallaroo.

The Brooksby gardens were home to wildlife whimsically introduced. Woollahra Digital Archive – PF 004631

There was considerable competition between the owners of the landmark gardens, and social occasions and charity openings were opportunities created to show off the grounds at key seasonal points. James Norton of Ecclesbourne was ‘a famous horticulturalist’ by Griffiths account, who planted ‘thousands’ of flowering bulbs around the lawns and embankments he fashioned from the sandy surrounds, giving a garden party annually when they bloomed.46

Ecclesbourne photographed in 1958. Photographed by Ian Scott. Woollahra Digital Archive – PF002283

Gardens without houses – Sir John Hay’s experimental garden

Two great gardens in the Double Bay area existed for part of their history independently of houses. One was Sir John Hay’s ‘experimental garden’, south-west of the Bay and set between Edgecliff, Manning and New South Head Roads. Hay’s garden took to new heights the Victorian vogue for horticulture as a gentlemanly diversion, both in the wealth of its collection of plant life, and in the luxury of dedicating land-use solely to the purpose of gardening as a pastime. This garden served neither any directly profit-driven purpose, nor the aggrandisement of Hay’s residence, which was situated several miles away, on the shores of Rose Bay – Rose Bay Lodge, once the home of Sir Daniel Cooper – where Hay lived among equally noted gardens, first laid out by John Gelding.

Extract from a municipal map of Woollahra circa 1889, showing Sir John Hay’s land at the junction of New South Head and Manning Roads

At no time would it appear that Hay planned to build more than the gardener’s cottage and sheds that were in place during his tenure of this garden. Nevertheless the garden was well known and a talking point in his time, due to the rarity of the specimens and the scope of the exercise. After his death, the land continued to support the growth established as the basis of two landmark properties, the Raine family’s Guyong, and Herbert Clarke’s Overthorpe. While Guyong was later developed, the value of Hay’s remaining garden at the Overthorpe property ensured the garden was preserved although the house was allowed to be demolished.

Gardens without houses – William MacDonald’s Mount Adelaide

William MacDonald’s Mount Adelaide, where garden preceded house, had a different history, with the estate sold before MacDonald created a dwelling fit for the setting he had provided. The property was located on the eastern side of Darling Point with a frontage to Double Bay, where MacDonald built a jetty for his establishment. The grounds were laid out in the 1830s by the great Thomas Shepherd – the only garden which can be positively attributed to him.

Shepherd’s commission included not only a pleasure garden, planted with pines and oaks, and an orchard laid out with several hundred fruit trees, but a terraced vineyard which sloped down the hill to the bay, and a series of ornamental fishponds, complete with islands, the waters controlled by an elaborate system of stone-walled canals and sluice-gates.47

MacDonald named his property Mount Adelaide, but it was left to later owners to build a house of that name.

Mt. Adelaide [Darling Point] [estate showing allotments for sale] – Courtesy of the State Library of NSW. M Z/M2 811.18114/1837/1

When MacDonald returned to England in 1837, he abandoned his property, leaving it for sale. The Darling Point section of the estate sold, and in 1843, Colonial architect John Mortimer Lewis built his Mount Adelaide house, as a fitting residence to grace McDonald’s Shepherd-designed gardens. Sadly the far more interesting follies on the Double Bay beach front had still failed to find a buyer when William MacDonald died in 1852

Few of the great gardens have survived, and those that have are generally much reduced in scale, and protected only through public ownership, planning restrictions, or an accommodating commercial purpose. Nevertheless, preserved in images and writings, the rich history of Double Bay’s garden associations remains part of the area’s cultural heritage.

From Steyne Park looking across Keltie Cove and Wiston Gardens to Darling Point, 1954. The sea wall, built in the 1930s, regulates the land at the edge of the beach, and the lagoon, now invisible, has become managed stormwater. The houses clustered to the left mark the area at the foot of William MacDonald’s terraced vineyard. Photographed by Carl Syme. Woollahra Digital Archive – PF008008

Published

Buckland, Jill Mort’s cottage, 1838 -1988. Syd., Kangaroo Pr., 1988.

Dowling, James Arthur ‘“Potts Point & Darling Point’ Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society 1906 Part III pp. 52-69

Griffiths, Glynde Nesta Some houses and people of New South Wales. Syd., Ure Smith 1949

Gross, Alan 'Guilfoyle, William Robert (1840–1912)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 4, Melb. Univ. Pr., 1972.

Jervis, James A History of Woollahra Syd., WMC 1960

Morris, Colleen Conservation Management Strategy: Overthorpe, gardens and grounds. Syd., The Author, 2010.

Morris, Colleen Lost gardens of Sydney Syd., Historic Houses Trust NSW, 2008.

Pescott, R T M W R Guilfoyle, 1840-1912 : the master of landscaping. Melb, Oxf, Univ Pr, 1974.

Collections

National Library of Australia TROVE database

- Newspapers and Gazettes

- Images, Maps and Artefacts

Woollahra Local History Collection –

- Digital Archive – Photographs

- Digital Archive – Local History Research Files

- Digital Archive – Woollahra Council Minutes

- Digital Archive – Assessments, Rates and Valautions

Footnotes

1 Jervis, James A History of Woollahra Syd., WMC 1960 pp 51-52.

2 Dowling, Arthur 'Some recollections of the New South Head Road and Woollahra' Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society Vol X, 1924 p. 47

3 Glenyarrah was the earlier name for Gladswood House which still stands on land above the eastern end of the Keltie Cove beach, where the storm water channel now discharges the former Double Bay Creek.

4 Dowling op.cit. pp. 54.

6 Sydney Morning Herald 19 November 1904 p. 4. [ The botanical names recorded in the text above are those provided by ‘E S’]

7 Op.cit.

8 British Map Engravers: a supplement, Peter Lewis Bemi

9 ‘Frazer, Charles 1788–1831', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 1, Melb., Melb. Univ.Pr., 1966.

10 Jervis, James A History of Woollahra Syd., WMC 1960 p. 51.

11 Sydney Morning Herald 14 April 1887 p. 4.

12 Local History Research File – Ridley, Thomas

13 NSW State Heritage Office – Media release 1999 following heritage listing of three La Perouse market gardens

14 Evening News 25 November 1903 p. 2

15 Maitland Mercury 18 June 1898 p. 13

16 Evening News 18 July 1887 p. 6

17 Local History Research File - Lough Playing Fields

18 1888 'The Women's Exhibition.’ The Daily Telegraph 29 September, p. 5.

19 The Sydney Morning Herald 24 January, 1890 p. 1.

20 ‘Nurseries of the Colony: Messrs J and W Gelding’s nursery’ The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser 23 July 1887, p. 164

21 Morris, Colleen and Clifford Smith, Silas, 'Gelding, John’, The Oxford Companion to Australian Gardens/ed Richard Aitken and Michael Looker Melb., Oxf. Univ. Pr./Australian Garden History Society 2002, p256.

22 The Sydney Morning Herald 10 March 1900, page 14; The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser 17 March 1900, page 625

23 NSW State Heritage Office, Camden Park and Belgenny Farm listing.

24 Morris, Colleen “Painting colonial plants: Epiphyllum species and hybrids” Australian Garden History Vol 18, No 5 May/June 2007 p. 9 (pp.6-9).

25 Waterhouse, Eben Gowrie Camellia quest. Syd., Ure Smith, 1947 p. 21

26 NSW BDM online index, refs: 1680/1852, V18521680 38A; 2210/1875; 9551/1876.

27 Sydney Mail and New South Wales advertiser 7 August 1880

28 Sydney Mail and New South Wales advertiser 19 January 1880 p. 68

29 Sydney Mail and New South Wales advertiser 6 August 1887 p. 278

30 Illustrated Sydney News14 April 1883 p. 3

31 Sydney Mail and New South Wales advertiser 6 August 1887 p. 278

32 Sydney Morning Herald 3 May 1902 p. 7

33 Pescott, R T M W R Guilfoyle, 1840-1912: the master of landscaping. Melb, Oxf, Univ Pr, 1974.

34 Waterhouse, Eben Gowrie Camellia quest. Syd., Ure Smith, 1947 p. 20-22

35 Morris, Colleen Lost gardens of Sydney p. 76

36 Australasian 6 May 1876 p 25

37 Buckland, Jill Mort’s Cottage, 1838-1988. Kenthurst, Kangaroo Press, 1988, pp.116-117, citing Sydney Morning Herald 9 November 1868.

38 Sydney Morning Herald 3 December 1868 p. 2.

39 Morris, Colleen Lost gardens of Sydney p. 91

40 Australasian 6 May 1876 p 25

41 Gross, Alan 'Guilfoyle, William Robert (1840–1912)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol 4, Melb. Univ.Pr. 1972

42 Illustrated Sydney News 23 December 1871 p. 12

43 Dowling, James Arthur ‘“Potts Point & Darling Point’ Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society 1906 Part III pp. 52-69

44 Morris, Colleen Lost gardens of Sydney p. 88

45 Griffiths, Glynde Nesta Some houses and people of New South Wales. Syd., Ure Smith 1949 p. 112

46 Griffiths, Glynde Nesta Some houses and people of New South Wales p. 127

47 Morris, Colleen Lost gardens of Sydney p. 88